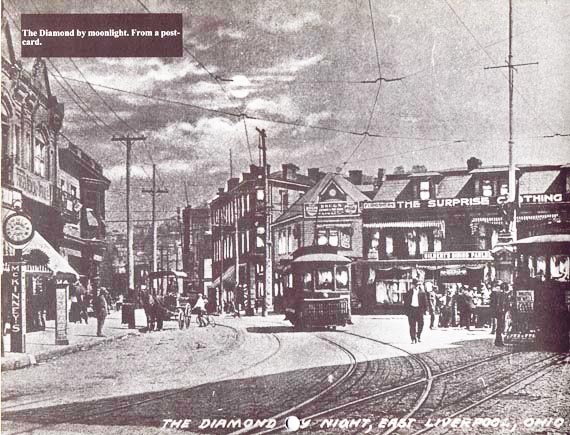

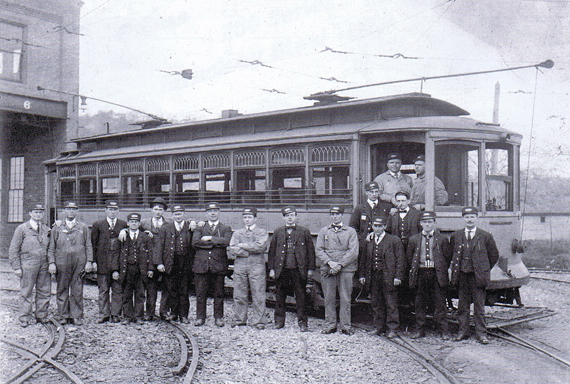

From the River Road the line went down second and up Market to the Diamond. The Diamond was the center of the various lines over the years. This picture was taken July 4, 1915. (ELHS)

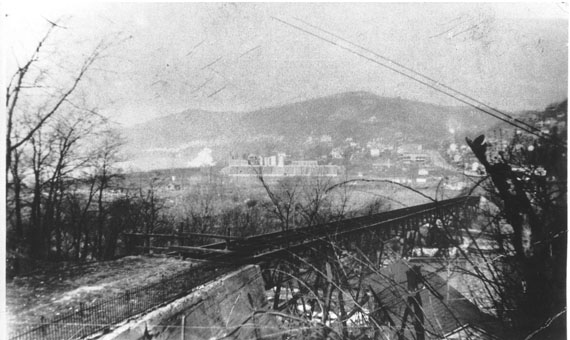

"Tripartite bridge to West Eighth Street"

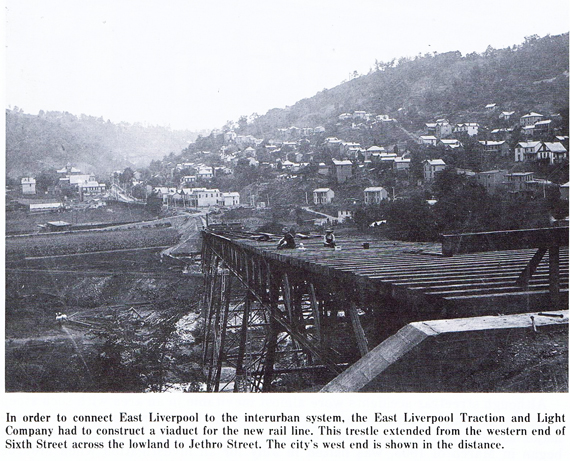

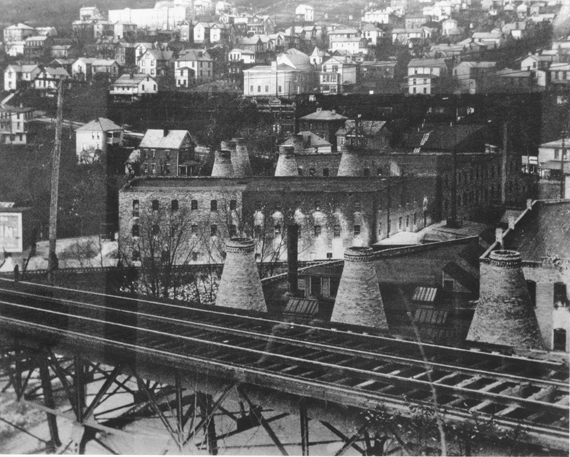

Its actual names were the "Tripartite bridge to West Eighth Street" or the "Sixth Street Viaduct." The double track bridge was part of the Ohio Valley Scenic Route which was part of the East Liverpool Track and Light trolley system which in turn was part of the Steubenville, East Liverpool and Beaver Valley Traction System.

For more information on the long gone landmark, see Ghost Rails III by Wayne A. Cole. pp 160-161 in particular and the entire book as a whole.

The viaduct was built in 1906 and was used until the early to mid 1930's when bus transportation began taking over the work of moving passengers. The viaduct was gone by 1940.

The construction of the Viaduct. This was a interesting feature of this system in East Liverpool.

As mentioned previously floods were a potential problem as shown here and in the next few pictures.

These pictures were of the 1907 or 1936 floods.

In its heyday.

The end nears. Not long after this picture was taken it was dismantled.

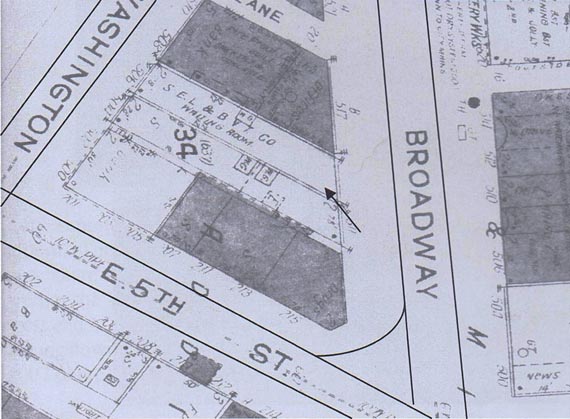

Broadway in East Liverpool. The green building and the white building were once upon a time a trolley station and waiting room as the map in the next picture show. Trolleys would back in the green building and discharge passengers and or take on new passengers.

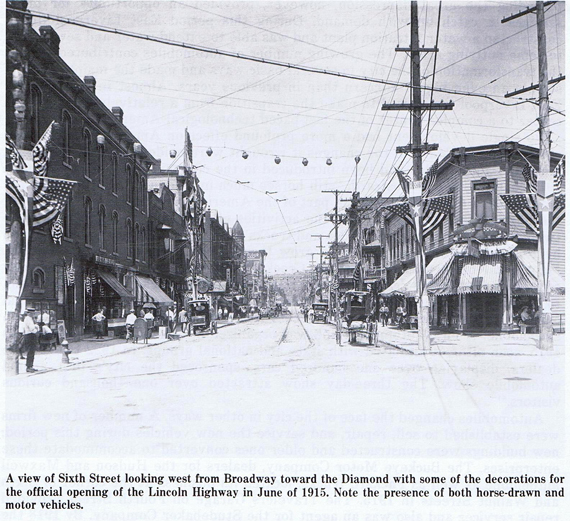

The most exciting event of the transportation revolution occurring during this period was the formal opening of the Lincoln Highway through East Liverpool in June of 1915. The thirty-three hundred mile Lincoln Highway was the first coast to-coast interstate in the nation and the "Crockery City" was proud to be located along its route. R.E. Spencer of East Liverpool was appointed official "moving picture" photographer of the Lincoln Highway Association and journeyed with the association on its coast-to-coast trip over the route. The editor of the Tribune considered this a grand opportunity for the future as the new road would bring thousands of travelers through East Liverpool annually. Aware that the city would be filmed during the automobile parade and celebration, the streets, houses, and businesses were decorated with flags and bunting. When the official caravan entered Ohio and East Liverpool on 5 June 1915 they were greeted by huge crowds and over one hundred additional automobiles joined the parade. Thousands gathered in the Diamond for a series of speeches and at 2:30 in the afternoon the former glass house kiln, which had been covered with pottery donated by the local potteries, was blown up in honor of the event.56

Also note that Trolley tracks were very much in evidence as well.

Almost as soon as gasoline-powered vehicles came into existence they were used, at least on a small scale, for public transportation in the city. In 1913 the Potters Motor Car Company offered overland transportation by automobile to other cities in the county. The City Taxi and Automobile Transfer Company operated three inter-city taxis by 1913. The LaCroft Transfer Company began service between the central city and suburbs north of the city in March of 1915. During a brief strike of streetcar employees in the spring of 1915, several jitney bus services began in East Liverpool. An editorial in the Review in October of 1919 told readers that inter-city public transportation had become a serious problem in cities across the nation. The editorial told of the experiment of substituting buses for trolley cars on the crowded east side of New York City. The buses, the article continued, eliminated overhead wires, tracks, and the "external jangle" of streetcars, however, increased hazards to pedestrians and the need for twice as many buses as trolley cars were considered drawbacks. Whatever the negative features of buses, the challenge to streetcar systems was unmistakable.57

In East Liverpool the transition from streetcars to buses was hastened by the years of disagreement between the city and the Steubenville, East Liverpool and Beaver Valley Traction Company and a strike in 1922. The traction company requested fare increases on its various streetcar lines in 1919. The request resulted in a wave of protest from East Liverpool and other municipalities served by the company. Following months of negotiations, the increases were granted, but when the traction company announced plans to discontinue service on certain lines it deemed unprofitable and to establish a zone system which would require a fare of fifteen cents between East Liverpool and Wellsville, the increases were withdrawn. The company actually discontinued service between the two cities in 1919 but was forced to re-establish it when Wellsville was granted an injunction prohibiting the action. The traction company petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to grant the increase because "interlocking ordinances and franchises in effect in valley cities prevented the establishment of increased fares." In August of 1920 the cities involved protested this action and were joined by the Ohio Utilities Commission who maintained that the Interstate Commerce Commission had no jurisdiction in the matter. The Federal agency ruled to grant the increase in December of 1921 following an investigation of the firm and the substantiation of claims by the company that it was operating at a loss. The restoration of a five cents an hour cut to employees of the streetcar line, as promised by the traction company if they were granted the increase, followed. The editor of the Review, trying to keep the peace, stated that it was generally conceded that the company needed the financial relief in order to operate and predicted, "there is expected to be little objection to the decision ......Several members of East Liverpool's city council did protest the ruling and Wellsville filed a request in Cleveland's Federal Court for a restraining order. The court ruled that the Interstate Commerce Commission had acted in excess of its authority in granting the increase and granted a temporary injunction. The decision was appealed by the traction company.58

During the time that the case was pending, the local situation grew worse. C.A. Smith, owner of the traction company submitted proposed wage reductions to his employees in light of the court ruling denying the fare increases. The workers refused the request and Smith announced that he would no longer recognize the union as a bargaining agent. Negotiations were suspended and on 1 May 1922 the employees of the traction company went on strike. Local automobile companies did not waste any time. The very next day the East Liverpool Motor Car Company advertised "Used cars for Jitney Purposes - Special Strike Sale." Traction company officials began negotiating with out-of-town men to replace the union carmen. As the editor of the Review pointed out the following day, the traction company was now "battling for survival." A similar dispute in Toledo, he said, had resulted in much more competition from buses and taxicabs once the streetcars there were returned to service.'5

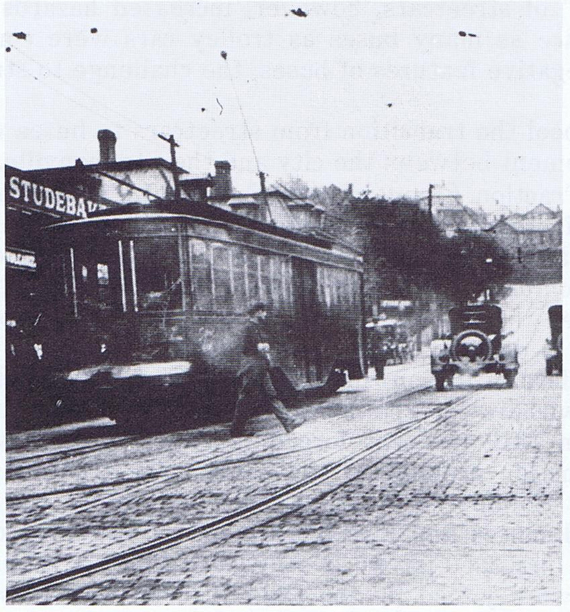

Fearing the automatic loss of his franchise if service was not continued and following the dictates of the court, Smith brought in twenty men to operate the cars and asked protection from Mayor Wilson. On 4 May a mob stopped a streetcar operated by "scabs" at the intersection of Broadway and West Fifth Street by disconnecting it from the electric wires. The mob, in a fever pitch, hurled rocks and bricks at the car and dragged the four operators from the car and began to beat them. The police rushed to the scene and eventually restored order. In the aftermath of the riot an estimated crowd of one thousand people surrounded the imported workers at the east end car barns and bombarded the building with rocks, breaking windows and lights. At 4:00 in the morning the workers were removed from the building under the protection of city and county police and left the city. Mayor Wilson ordered the traction company to cease operating the streetcars and the following day Common Pleas Judge J.G. Moore granted the mayor's request to lift the court order requiring the restoration of service.

Streetcar at the intersection of Broadway and Fifth Street shortly after a riot related to the streetcar strike. A witness said an "enormous crowd" converged on the car and stopped it. "Screaming and yelling," he said, they threw bricks at the window and "beat up" the operators. As one man ran away he was hit with a brick and fell to the ground. The witness said one group pulled one "scab" to the Chester Bridge to throw him off but reconsidered their action and released him. Hills and Kilns p 287.

By 13 May 1922 the Tribune reported "more than 120 buses and taxicabs are now doing business in the city streets ....The editor also hoped, however, that city council would act to end the strike. He said, "A survey among representatives of union labor and the city's business interests shows pronounced sentiment for prompt financial relief for a traction line that is losing money." Although some people welcomed buses because they were "modern," others were afraid of them and did not trust them on the city's steep hills in icy weather. They were also reluctant to abandon an efficient system that had operated for years in a very punctual and reliable manner. City council attempted to reach a settlement but as long as Smith continued to ignore the carmen's union the strike continued. By mid-July calls for a settlement were frequent. With no evidence of a settlement at hand, city council took steps to secure a bus franchise for the city. In the meantime East Liverpool's council passed the second reading of an ordinance granting fare increases. Wellsville's city council, however, failed to institute a similar ordinance stating that they would not enter the situation until Smith settled with his employees. One Wellsville councilman believed that a franchise should be granted to a bus company and . . put the traction company out of business forever." The ordinance was defeated in East Liverpool's council chambers on the final reading."

The debate and the strike continued throughout the rest of the summer. On 21 September East Liverpool's council passed an ordinance granting fare increases to Smith's company. The ordinance also stipulated that the firm could not withdraw service on any lines but could substitute a "bus service or trackless trolley" on the River Road line. Smith, however, refused to accept this provision as he had three years earlier. When the city sought to force Smith to operate the line through a court injunction, the request was denied. The ordinance question raged for an additional two months. The federal court in Toledo upheld Wellsville's injunction against the traction company in November of 1922. Two weeks later Wellsville's council finally passed an ordinance increasing fares; following an "unexpected turn of events" East Liverpool did the same on 29 December 1922. When all the dust had settled, a two-zone system with a one cent transfer charge was established. A trip from anywhere in the "Crockery City" to any point in Wellsville cost eleven cents rather than the fifteen cents originally proposed almost three years earlier. The traction firm was also granted the right to establish a bus line in place of the streetcars on specific lines. The traction company opened jobs to all its former employees and reinstated the wage increases it had taken back 241 days earlier. In January of 1923 the streetcar system was once again operational. Wellsville received a jolt in January of 1925 when the United States Supreme Court upheld the jurisdiction of the Interstate Commerce Commission and its authority to grant the traction company the right to operate under a three-zone system. This ruling, however, came too late to affect the situation .62

By the summer of 1923 both streetcars and buses were operating intercity and intracity routes. In March of 1924 the State Utilities Commission granted a charter to the Valley Motor Transportation Company, a subsidiary of the Steubenville, East Liverpool and Beaver Valley Traction Company, to operate buses in the district.63 C.A. Smith controlled both firms. Weary of the controversy and the protracted strike, the residents of East Liverpool adjusted gradually to the use of buses for mass transportation in the community. During the balance of the decade both streetcars and buses transported people to work, to the business district, and home again. (The city of Hills and kilns, pp 288-291)

East End Car Barn.

The Trolley Transportation Days 4

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law

though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.