| Information from The City of Hills and Kilns, pp. 306-308. |

East Liverpool was represented in both baseball and basketball semiprofessional leagues during this period. The Ohio and Pennsylvania Baseball League, which had an East Liverpool team for years, disbanded following the 1912 season. A new independent club was organized for the next season. Known by a variety of names, including the "Man 0 War team," they played rivals from a five-state area throughout most of the 1920s. Frank D. Allison sponsored a basketball team in the city and was able to obtain a franchise in the American Basketball League in 1925. The East Liverpool team joined Cleveland and Canton as Ohio's representatives in the league and Allison recruited seven "proven stars of national prominence" from eastern cities. Although spectators enjoyed the games played in the city, identification with a local team was missing.

Enthusiasm for local teams was reserved primarily for those of the high school and YMCA Industrial Leagues. In 1926 more than eight thousand fans jammed the athletic field for the annual East Liverpool - Wellsville football game which had been suspended for four years because of roughness. The "Potters" defeated their down-river rivals by a score of thirteen to six. Basketball also became very popular and the high school had some excellent teams during this period. In 1916 East Liverpool was second in the state, losing only to Dayton in the championship game. The high school basketball team was the champion of Columbiana County in 1922. The board of education had been attempting to purchase land to develop an athletic field for several years when in January of 1924 Monroe Patterson donated seven acres in the city's west end. Patterson, founder of the Patterson Foundry and Machine Company and part owner of the Wellsville China Company, made the donation in order to ". . . provide the present and future children of East Liverpool with a suitable and convenient place to play and indulge in clean sports." He also specified that it be used as an athletic and recreational field "forever." The site was dedicated as Patterson Field in November of 1924 before a football game. One week later Patterson, who also constructed a four-story home for women as a gift to the city and a memorial to his wife, died. The Mary Patterson Home, which had 116 furnished rooms, a swimming pool, and a variety of public rooms including a lounge and auditorium, was completed in 1925 but was not occupied until 1932.

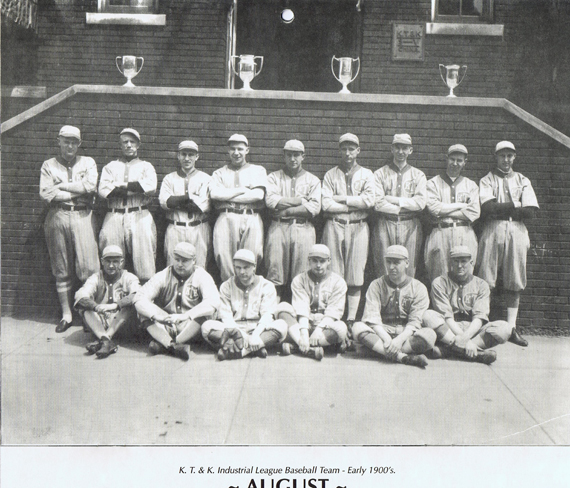

The city received another recreational institution in 1911 when $100,000 was raised by local donations to build a new YMCA building on Fourth Street. The editor of the Review called the accomplishment, "The greatest civic movement in the history of East Liverpool." The fund raising campaign was supported by all of the potteries including the Homer Laughlin China Company which donated five thousand dollars and at least ten individual donations of twenty-five hundred dollars each. The new facility was opened to the public in February of 1914 and was immediately popular, attracting ten thousand to gymnastic classes and over thirty thousand to the swimming pool during the first year. Starting in 1921 the YMCA organized a series of industrial competitions including boxing, wrestling, relay racing, volleyball, and a tug of war between various local firms. The YMCA also sponsored industrial leagues in bowling, horseshoes, and basketball. The most popular league in East Liverpool, however, was the YMCA Industrial Baseball League. Organized in 1921, the league included teams from the following potteries: Edwin M. Knowles China Company; Homer Laughlin China Company; C.C. Thompson Pottery Company; The Potter's Co-operative Company; Knowles, Taylor and Knowles; Hall China Company; and Taylor, Smith and Taylor. The league played a fifty-six game schedule averaging three games per week. An estimated five to six thousand spectators attended the games. Competition became fierce and most sponsoring potteries began to hire workers based on their skill on the diamond rather than at the bench. In 1925 the YMCA eliminated its industrial league activities because of the importation of "outside" players to replace less skilled potters; as a result the players formed a private industrial league. The City Industrial League continued playing throughout the balance of the decade, attracting thousands of fans. Even the players and sponsors eventually realized the negative aspects of importing talent to insure victory and in 1928 they adopted a "home talent" rule.

A number of the area's most prominent executives began plans to establish a country club in October of 1919. They formed two corporations, the East Liverpool Country Club and the Saint Clair Land Company, and purchased a ninety-five acre site north of the city. This coincided with a national movement to establish country clubs. Benjamin Rader, a noted sports historian, said the country club in the twentieth century "became a haven for those seeking to establish status communities in the smaller cities . . . most clubs were composed of status-conscious old-stock Americans." The East Liverpool Country Club opened to over four hundred members and guests in July of 1921. It contained a nine-hole golf course, two tennis courts, and a clubhouse which included a dining room, a ballroom, and appropriate facilities for sporting activities and maintenance of the grounds. The country club became a center for the social life of its members. The most important sport encouraging the spread of the country club throughout the nation was golf. In April of 1921 Patrick McNicol of the Standard Pottery Company, Charles Ashbaugh of the West End Pottery company, and several others traveled to Indiana for golf instruction in reparation for the opening of the country club. Other members did not require instruction. Joseph M. Wells, President of the Homer Laughlin China Company, on the state amateur golf title in 1922 and in 1924. Although East Liverpool's wealthier residents aided the city in general through philanthropic gestures like that of Monroe Patterson and by donating generously to campaigns such as the YMCA building drive, they also sought to establish their own havens and keep the lines of social stratification tightly drawn.

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.