| This article by Timothy R. Brookes appeared in TIMELINE. JULY - AUGUST 1998 A Publication of the Ohio Historical Society, Volume 15/Number 4 pp 18-25 |

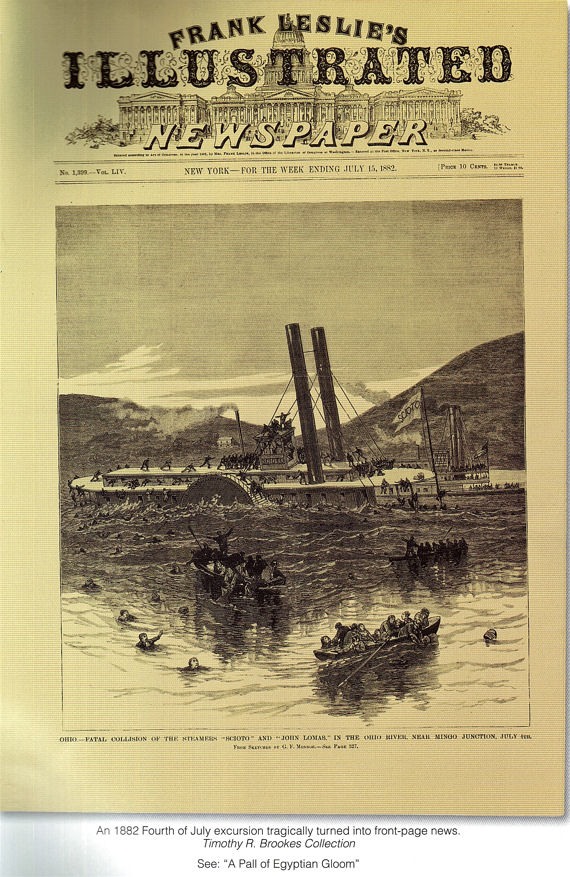

A PALL OF EGYPTAIN GLOOM: THE SINKING OF THE "SCIOTO" by Timothy R. Brookes

"The Fourth of July, to many a family in Wellsville and East Liverpool, will be in the future, instead of a red-letter day, a day of mourning and sadness." With these words, in the summer of 1882, a reporter for a Wellsville weekly summarized the worst river tragedy ever to occur on the Upper Ohio. What began as a day's excursion trip on one of the many steamboats plying those waters ended in a calamity that took the lives of one in every ten passengers aboard.

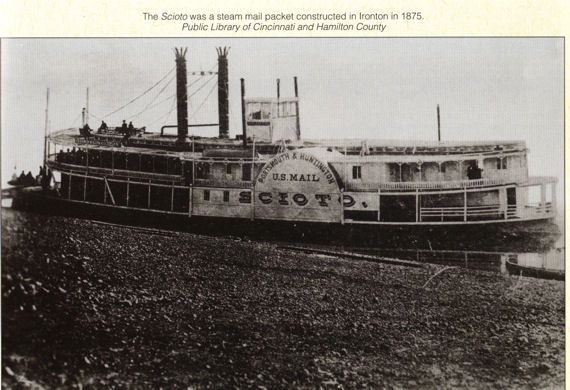

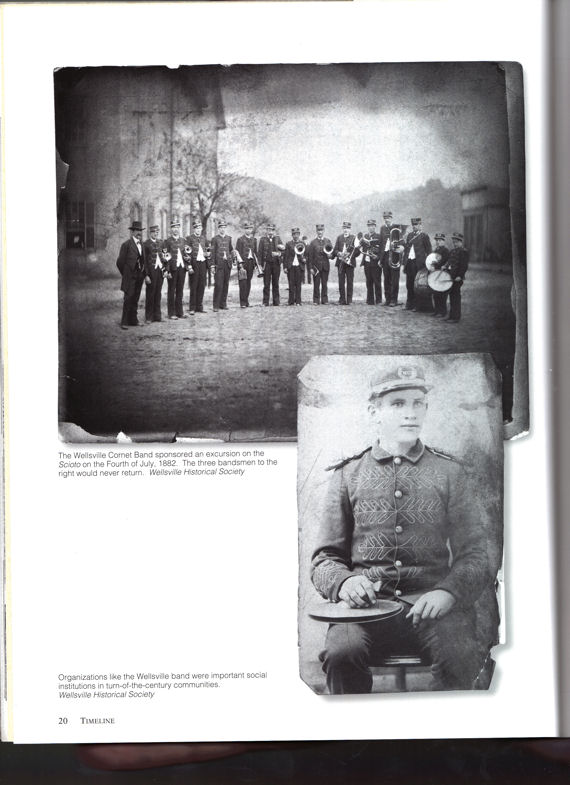

The excursion was sponsored by the Wellsville Cornet Band. Billed as a day-long trip to Moundsville, West Virginia, (where visitors could tour the State Penitentiary) the outing attracted numerous young people. Chartered for the junket was the side-wheel steamer "Scioto" commanded by Captain Thaddeus Thomas.

On the morning of the 4th, a Tuesday, the "Scioto" began loading its passengers at the East Liverpool wharf. Nearly four hundred persons were reported to have crowded aboard the craft, which was licensed to carry sixty.. Stops at Wellsville, where the band boarded, and at Steubenville, added another one hundred or more passengers to the already overloaded vessel. The trip downriver was made without incident. The Excursionists reached Moundsville about 1:00 p.m and passed several hours with sightseeing, picnics, dancing and, if later accounts were not exaggerated, considerable consumption of alcohol.

The return cruise began shortly after 5:00 p.m. Captain Thomas, concerned by the overloading, ordered reduced steam to lessen the danger of a boiler explosion. Merrymaking continued on board with the band's best efforts fueling the dancers' energies.

About eight o"clock, as the Scioto neared Mingo Junction, another craft approached from upstream. According to accepted navigational practices, the descending boat had the right to choose position when meeting another Vessel. B. J. Long, the pilot of the oncoming "John Lomas", blew one long blast on his steam whistle signifying his intention to hold his position near the Ohio shore.

John Keller, piloting the "Scioto", was at the wheel and, upon hearing the whistle of the "John Lomas", should have then eased the vessel toward the West Virginia shore. This he failed to do, later claiming that the signal was late in coming. Instead, he sounded two blasts of the Scioto's whistle claiming the same favorable position.

Although the accounts of the interested parties were contradictory, witnesses on shore stated the the "John Lomas" made her intentions clear in adequate time and that the "Scioto's" response was tardy. Keller's last minute order to reverse engines came too late to avoid disaster.

The vessels collided at speed tumbling many of the dancers and musicians on the "Scioto", who had not noticed the impending collision. The "Lomas" struck the port-side of the "Scioto", tearing a large hole below the water line.

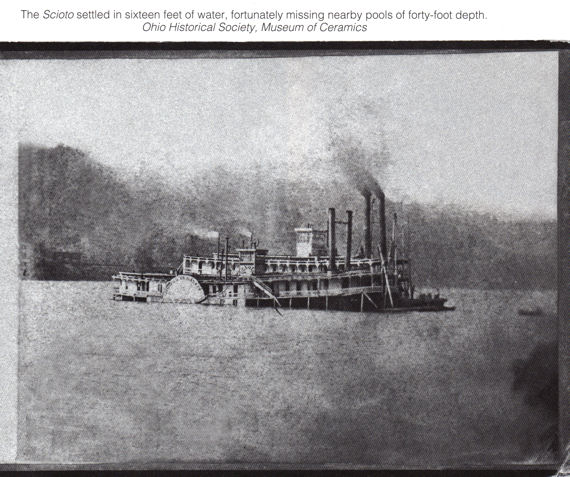

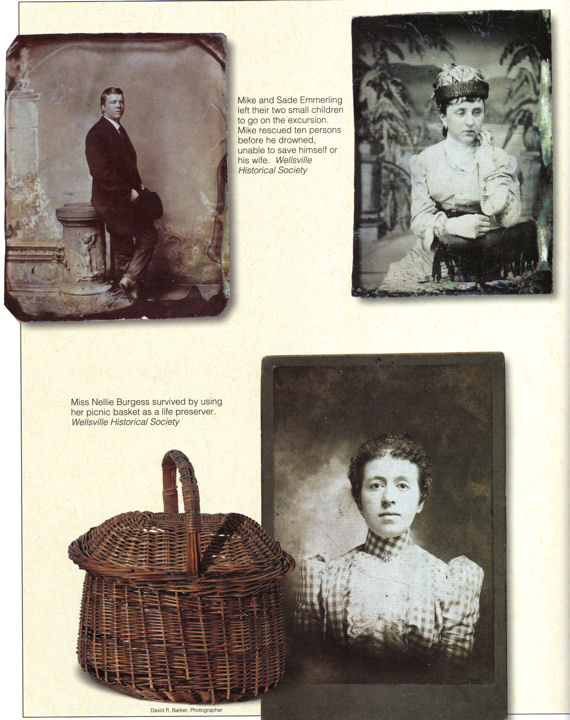

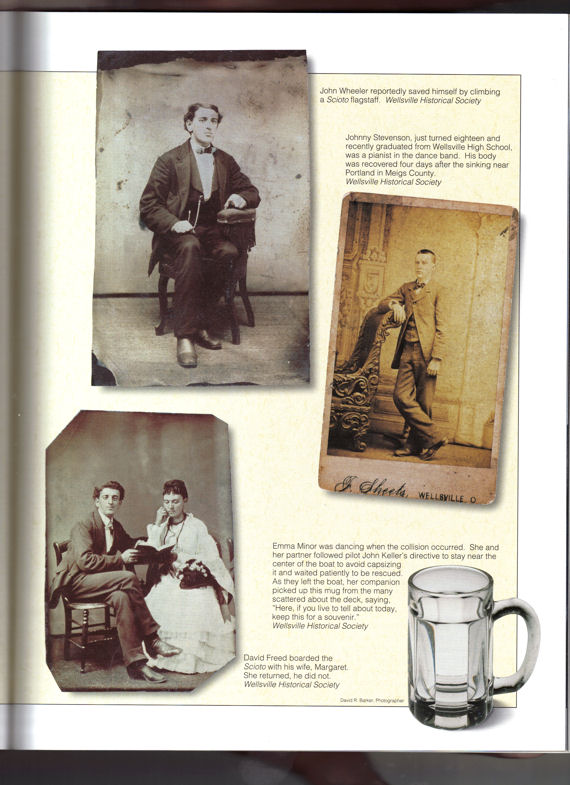

The "Scioto" sank almost immediately in sixteen feet of water. The "Lomas", after first discharging its passengers on the riverbank, returned to help rescue survivors. Panic increased the death toll as many passengers on the "Scioto" flung themselves into the water to avoid an imagined outbreak of fire aboard the sinking craft. While some were trapped in cabins and thus lost their lives, most of the victims perished after falling or jumping into the river. Many of the survivors climbed to the "Scioto's"upper decks, which remained above the surface. Several of the victims drowned while attempting to save fellow passengers. The death toll eventually totalled fifty-seven.

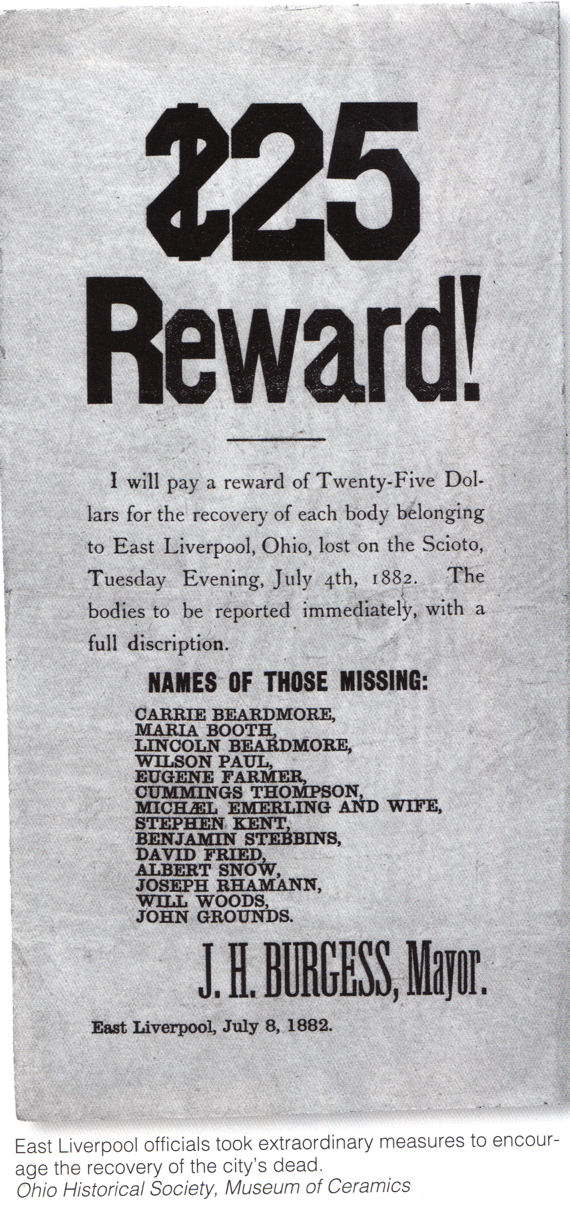

News Of the disaster reached Wellsville by 10:00 p.m. and a special train was immediately dispatched to bring back survivors. The search for bodies began in earnest the next morning and continued for several days. Fifty men from East Liverpool worked at grappling operations until Sunday, July 9/ By then most of the victims had been found. The Wellsville "Saturday Review" reported that "East Liverpool and Wellsville have indeed been in sackcloth and ashes." Business was suspended in both cities, and " A pall of almost Egyptian gloom has rested over all....nobody has the heart to work. Scarcely anything has been thought of or spoken of but the calamity that came so suddenly upon us."

Many of the drowned were in their teens, including two members of the band, ages thirteen and fifteen. Brothers William and Joseph Beardmore, of East Liverpool, each lost two children in the disaster. Captain Thomas, who was not in the pilothouse at the time of the collision, lost a fifteen-year old son and had to be restrained from suicide. In time, all of the bodies were recovered.

As might be expected, attempts to fix the blame were initiated before all the funerals had been concluded. The organizers of the excursion were criticized for "employing so miserable a little craft for such an occasion, and then allowing so many to take passage". Captain Thomas was similarly chastised by the press

Most of the culpability was, however, placed on the pilot of the "Scioto". He was described as "utterly unfit and incompetent," a Wheeling saloonkeeper rather than a full-time river pilot. Keller admitted to having consumed at least one drink that day and was charged with having permitted female passengers to enter the pilothouse.

Both pilots were suspended after the accident but were later reinstated. Public opinion in East Liverpool and Wellsville was so strong that Keller was eventually convicted of drinking, failing to answer Long's signal, and permitting passengers to enter the pilothouse. He was allegedly sentenced to a prison term for his neglience. To insure that such a tragedy was not repeated, the government changed the passing signals and revised the steamboat inspection laws.

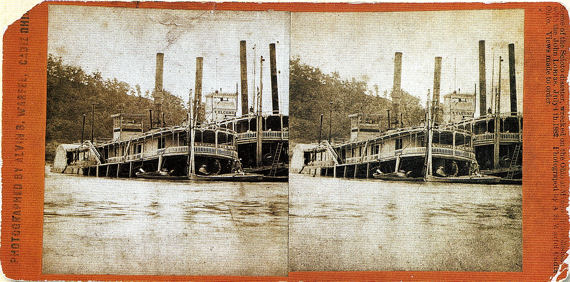

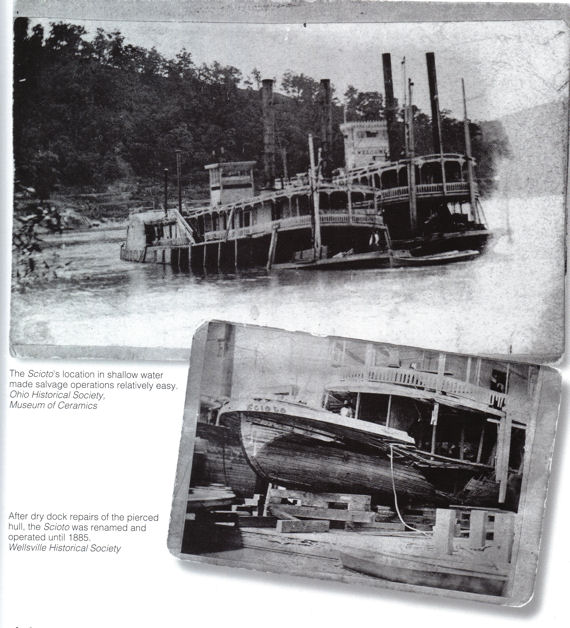

The "Scioto" was raised and repaired after the sinking and continued in service under the name "Regular" until 1885 when she was scrapped. The "John Lomas", unhurt in the collision, was transferred to the Kanawha River and remained in service for many years. A poignant reminder of the human loss appeared in print some time after the accident, when the "Saturday Review" printed the following: "Anyone possessing a picture of the late Miss Sarah Kiddy [who was celebrating her sixteenth birthday on July 4] will confer a great favor on her mother by giving it to her, as she has none."

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

DROWNED BY A COLLISION; A STEAM-BOAT DISASTER ON THE OHIO RIVER. July 5, 1882, Wednesday PITTSBURG, Penn., July 4.

http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9E00E0DB173DE533A25756C0A9619C94639FD7CF

SCIOTO --from the Wheeling Intelligencer, July 5, 1882, p. 1 DIRE DISASTER SINKING OF THE STEAMER SCIOTO

http://wheeling.weirton.lib.wv.us/history/bus/river/scioto1.htm

SCIOTO from the Wheeling Intelligencer, July 6, 1882, p. 1 THE SCIOTO DISASTER. SCENES AT THE WRECK YESTERDAY

http://wheeling.weirton.lib.wv.us/history/bus/river/scioto2.htm

SCIOTO from the Wheeling Intelligencer, July 10, 1882, p.1 THE SCIOTO DISASTER. STILL GRAPPLING FOR THE DEAD

http://wheeling.weirton.lib.wv.us/history/bus/river/scioto3.htm

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.