| This article originally appeared in the 1976 Tri-State Pottery Festival Souvenir Program |

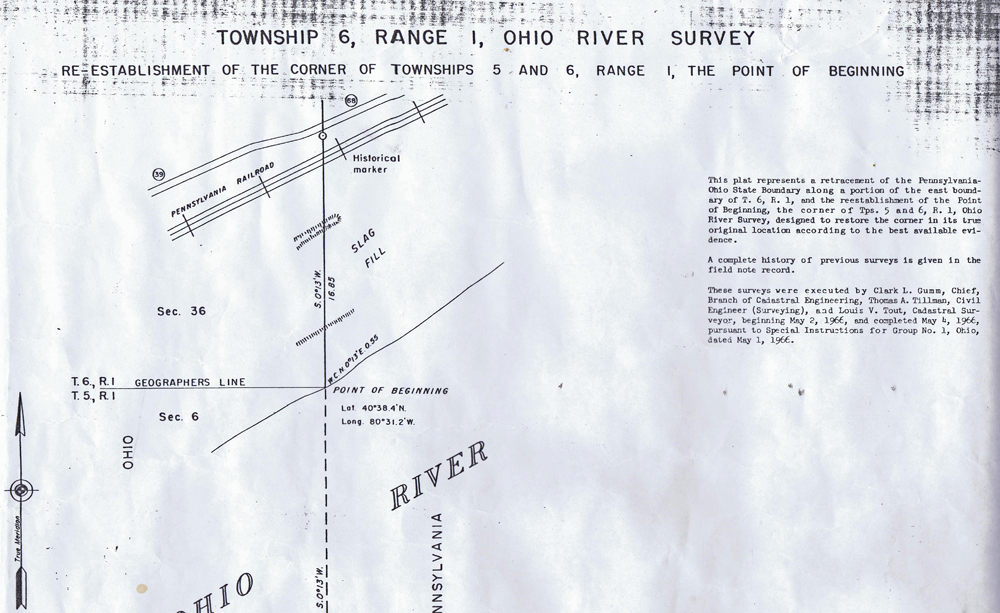

In 1785, Thomas Hutchins and his men began the United States Survey of Public Lands at a spot registered and dedicated in 1966 by the Historical Society with the Department of the Interior. The Surveyor's line entered East Liverpool through Dixonville, north of the Riverview Greenhouse, through Riverview Cemetery onto St. Clair Avenue at Blackmore Street and Maplewood, Although the going is rough because of brush and undergrowth, it is possible to walk the line. The monument is located on Route 39 East and is maintained by the Historical Society.

The Point of Beginning and The Seven Ranges

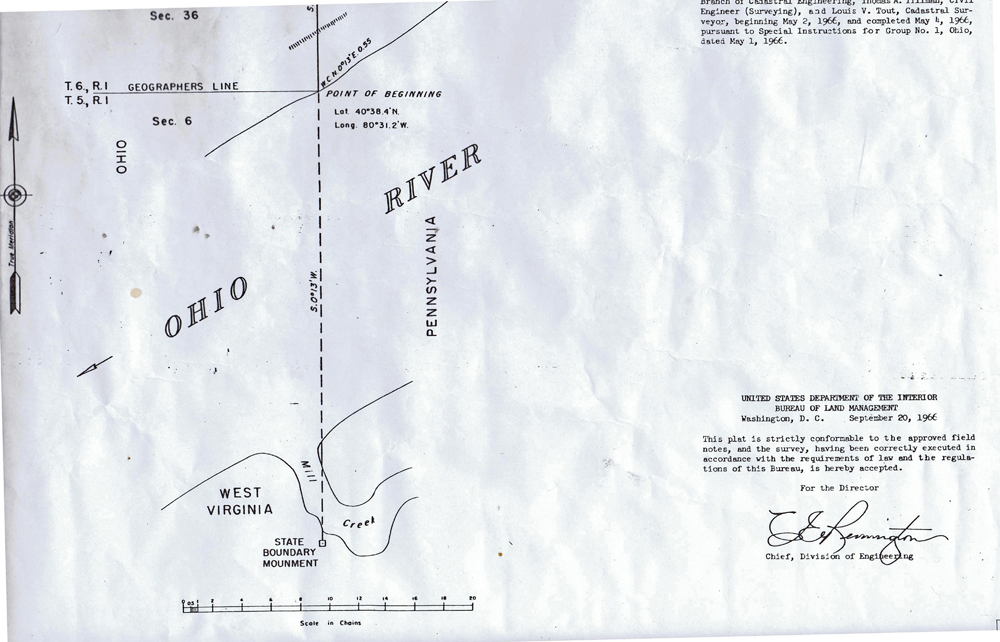

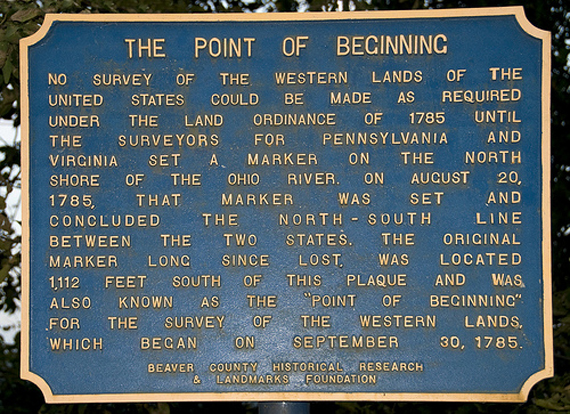

Among our National Historic Landmarks, one that ranks high in significance stands at the south-east corner of Columbiana County, Ohio, on the Ohio-Pennsylvania Line. It marks "The Point of Beginning" of the American Rectangular Land Survey System by the Federal Government in 1785. This Rectangular System eventually extended across the continent and now includes Alsaka and Hawaii. It is most apparent in the plains area where roads and fences run north to south and east to west. The present monument was set at the river's edge in 1881 when the Ohio-Pennsylvania boundary was re-surveyed and re-marked (the original marker of 1785 had disappeared). When, in recent years, the monument was endangered by land fill along the river, it was moved (1960)1112 feet north to the safety of high ground near the River Road between East Liverpool, Ohio and Midland, Pennsylvania. There it is easily accessed by all who wish to read the story it tells.

West Face -Ohio

"1112 feet south of this spot was the "Point of Beginning" for surveying the public lands of the United States.

There on September 30, 1785, Thomas Hutchins, first Geographer of the United States, began the Geographer's Line of the Seven Ranges. This inscription was dedicated September 30, 1960, in joint action of the East Liverpool Historical Society, and the American Congress on Surveying and Mapping."

East Face - Pennsylvania

"Erected in 1881 by a joint commission appointed by the states of Pennsylvania and Ohio to re-survey, and re-mark the boundary line as established in 1786."

In 1966 the "Point of Beginning" monument was approved by the Department of the Interior of the United States Government and dedicated with appropriate ceremony by Jerry O'Callahan, the Chief of the Geodetic Survey, as a Registered National Historic Landmark. A plaque on its north face records its new status under the National Park Service.

When our National Independence was confirmed by the Treaty of Peace with Great Britain in 1783, the Continental Congress fell heir to the first public domain, the Northwest Territory. The Congress was interested in selling land and there were groups of men who were eager to buy but that Territory was occupied by several tribes of Indians who were in no mood to move.

After months of debate Congress decided to sell no land until it was surveyed and to do no surveying until the land was purchased from the Indians. Then they spelled out what they meant by "purchased". The Indians were to be paid in "coarse trade goods, clothing and other articles." While the Indians always eagerly accepted gifts they never understood or willingly accepted the idea of selling land.

A committee was appointed to find a way to persuade the Indians to sell on government terms. The Committee decided that the Indians were obligated to yield "as atonement for the enormities they have perpetrated, and as a reasonable compensation for the expenses the United States have incurred by their wanton barbarity".

Having justified to themselves what they intended to do, the committee then recommended a dictated treaty that would require all the tribes to move west of the Great Miami and Maumee Rivers, vacating nearly all of the present State of Ohio. In the meantime, some of the stronger tribes, encouraged by the British who still held Detroit, had united in a declaration that the Ohio River should be the boundary between the whites and the Indians forever.

Faced by this stand on the part of the Indians the committee changed its tactic to one of "divide and conquer": Perhaps a foothold might be gained by picking off some of the lesser tribes first, and that is just what happened.

At the request of the Committee on Indian Affairs, chaired by Thomas Jefferson, representatives from the Delaware, Ottawa, Chippewa and Wyandot tribes reluctantly attended a parley at Fort McIntosh on the present side of Beaver, PA in January 1785. Surrounded by more than 200 militia, who had been called up for the occasion, they were entertained with rum and feasting and given presents and, most likely while intoxicated, they were persuaded to surrender their claim to about half of the present state of Ohio. Immediately these tribes found themselves between two enemies, the whites on the east and the other tribes on the west who refused to accept the Ft. McIntosh deal. One Indian spokesman said to commissioners, "we are between two fires; we are afraid of you and likewise of the back nations".

The Commissioners on this occasion were Richard Henry Lee, Richard Butler and George Rogers Clark, all army officers. Here a precedent was established. All later treaties with the Indians were negotiated by the military.

The Ft. McIntosh treaty, so-called, was a prerequisite to an Ordinance adopted soon after by Congress to begin the survey of the Northwest territory. Behind that Ordinance there was a duel motive. First, Congress wished to dispose of the public land in an orderly manner, rather than by squatter's choice. South of the Ohio River settlers had staked their claims and had them surveyed later. Consequently there were many boundary disputes and faulty land titles. Abraham Lincoln said the main reason his family left Kentucky was difficulty with land titles. Congress did not mean for that to happen again. Also Congress anticipated much needed revenue from the sale of land to help support the government and pay the war debt. The Constitution had not yet been written and Congress lacked authority to collect levies from the states. Sometimes Congressmen had to pay their own expenses.

Thomas Hutchins, then government geographer, and who had already explored the Ohio Valley, was appointed chief surveyor. All the states were invited to choose their own surveyors to assist him. This was to permit the states equal opportunity to size-up the land in view of later purchase for settlement. Actually, only eight state surveyors appeared. These men have been called "gentlemen surveyors" because they were chosen more for their ability to evaluate the land than for their experience as surveyors.

Late in the summer of 1785 Hutchins and his eight assistants made the arduous two-weeks journey over the mountains to Pittsburgh, then a cabin village of about 300 people. Hutchins' first act was a canoe trip down the Ohio to consult with Col. Harmar at Ft. McIntosh about the Indian situation. He was assured that he could "very safely repair with his surveyors to the intersection of the Pennsylvania line with the river".

With that assurance Hutchins returned to Pittsburgh, here he bought supplies and hired chain carriers and ax men. It was the last week of September when his party of about 30 men, with horses and equipment, pitched their camp on the north shore of the Ohio River between Little Beaver Creek and the Pennsylvania line. This Pennsylvania line, which had been surveyed and marked only a few weeks previously, gave them their starting point. Congress had directed Hutchins to begin at the junction of the Pennsylvania line and the Ohio River and that he himself should run a base line straight west. At six mile intervals along that base line perpendiculars should be dropped to the river creating tiers of townships or ranges.

As the ax men cleared a path the survey began September 30,1785. From the beginning the work was difficult and slow. They found the land cut by deep valleys with sides so steep that only a few feet at a time could be measured on the horizontal. One surveyor wrote later, "Before I had gone a mile I discovered that is was impossible to do accurate chaining in such broken country where the hills were so steep it was often with difficulty that they could be climbed." In eight days they had advanced less than four miles when they heard of an Indian attack somewhere to the west. Hutchins, always cautious and wary of the Indians, ordered a retreat and moved his camp to the south shore of the river.

It had been understood that soldiers from Ft. McIntosh would provide protection for the surveyors. However, the day before the survey began the whole force from the Fort floated down the river to a meeting with the Shawnee tribe in the Scioto river area. Also Hutchins had sent messages to the Delaware and Wyandot Indians asking for two chiefs to protect his men from roving red men. As one might expect no chiefs appeared. After all the preparation only eight days' work had been done that first season and the surveyors went home. Later it was learned that the Indian attack which halted the work had occurred at Tuscarawas nearly 50 miles away; a trading post was wrecked and one man was killed.

The second season all the states but Delaware were represented, making a total of 13 surveyors. Again they started late because Hutchins refused to proceed without protection and Col. Harmar was reluctant to send soldiers into the area for fear of stirring up the Indians. Only after an order from the Secretary of War did he send about 150 men. Most of them, however, remained in a camp on the river due to lack of equipment; only about 30 accompanied the surveyors, too few for adequate protection as they spread out over the several ranges.

One incident occurred when some horse were stolen, but no man was harmed. The work moved along at a good pace and on September 18 they reached a point 42 miles west from the Pennsylvania line, the width of seven ranges.

The next morning they found the last stake driven the previous day broken and red paint smeared on a tree – Indian warnings. The same day a soldier from the river brought a message that the Shawnees, sworn enemies of the whites, were gathering to "cut Hutchins off with all his men." Again the surveyors retreated; this time to Cox's Fort, a group of cabins surrounded by a stockade, near present Wellsburg, West Virginia. When, after waiting two weeks, no Indians appeared, they resumed work until bad weather in November. Again the surveyors returned to their homes in the East except Hutchins and two others who remained at the home of Wm. McMahon at Cox's Fort to organize their field notes. This was more than the usual surveyors task because they were required to record their observations of the quality of soil and timber, of streams suitable for mill sites, evidence of minerals -- coal, iron and other information of interest to prospective buyers when the land was sold at auction in New York. After Christmas Hutchins returned to New York, leaving the completion of the seven ranges to others.

Two of the surveyors wintered in the valley. The following spring they resumed work in April and a few days later three others from the East joined them. Again some horses were stolen, but no man was harmed and the survey of the Seven Ranges was completed in July 1787.

The threatened Indian attack of the previous season failed to occur because at just that time a party from Kentucky raided and destroyed the Shawnee villages in retaliation for raids the Indians had made into Kentucky.

Mention should be made of the settlers on the South shore of the Ohio River who aided the surveyors with produce from their farms, with men and horses and shelter when needed. Among them were names still familiar in the area -- Dawson, Wells, Cox, Greathouse, McMahon in the upper valley and Ebenezer Zane at Wheeling.

That was the end of government surveying for a decade. Financially the project was disappointing; land sales were slow. It had taken three times as long and cost almost three times as much as expected. Congress had appropriated $5,000.00 and apparently expected the job to be done in a single season. Due mainly to fear of the Indians it had extended over three seasons and cost almost $15,000.00.

A pertinent item appeared in the press by columnist Bill Vaughn. He said, "a successful government program is one that costs only three times as much as the estimated ceiling and twice as much as anybody's wildest dreams." The precedent was established by the very first major project undertaken by our Federal Government.

Congress then did an about-face. Instead of limiting land sales to township and section lots they began selling to large volume buyers, the Ohio Company at Marietta and Symmes Purchase (Miami Purchase) between the Miami Rivers. They were required to do their own surveying and three of the better qualified surveyors worked for them, benefitting from their experiences on the Seven Ranges.

The career of Thomas Hutchins came to rather abrupt and unexpected end. He had made his contribution to our de, floping government as its first surveyor. As geographer he had made the most accurate map to date of The upper Ohio Valley and its tributaries. He had proposed to Congress the extension of the map to the Mississippi, but congress was always short of money and nothing came of it.

Gradual alienation from government service followed a long and frustrating hassle with Congress over the pay for himself and his surveyors on the Seven Ranges. He also began to doubt the possibility of settling the land north of the Ohio River against Indian resistance. As Hutchins phased out his government service he became involved with a wealthy merchant, George Morgan, in a plan to settle a Colony west of the Mississippi in Spanish territory. He also offered his services to the Spanish governor at New Orleans to survey and map the Mississippi River.

His own death saved Hutchins from the possible consequences of a questionable involvement with a foreign nation. After several months' illness he died on April 28, 1789 before his offer to Spain was accepted.

Thomas Hutchins was buried in Pittsburgh, but the location of his grave has eluded all searchers. His only monument is the five foot stone which marks the "Point of Beginning" of the first government survey in the United States and credits Hutchins as the surveyor. County maps in the area of the Seven Ranges still show the base line, surveyed by Hutchins, labeled "The Geographer's Line," in honor of the surveyor.

On a fine winter day I explored the first three miles of The Geographer's Line. Three miles as the crow flies; on foot it must be four. After nearly two centuries the area is still quite wild and difficult to traverse. Although the original timber is gone the land is covered by trees, bushes, and briers, often so matted with vines that only a bird could penetrate. The valleys are deep and hills so steep that still "only with difficulty can they be climbed." Although long accustomed to hiking, those three miles required four hours of hard work. Conclusion: The surveyors earned their two dollars per mile.

— From the historical files of Dr. C. M. Mayberry —

IMAGES POINT OF BEGINNING

THE LIFE OF A SURVEY MONUMENT

http://www.blm.gov/ca/flash/fb/survey.html

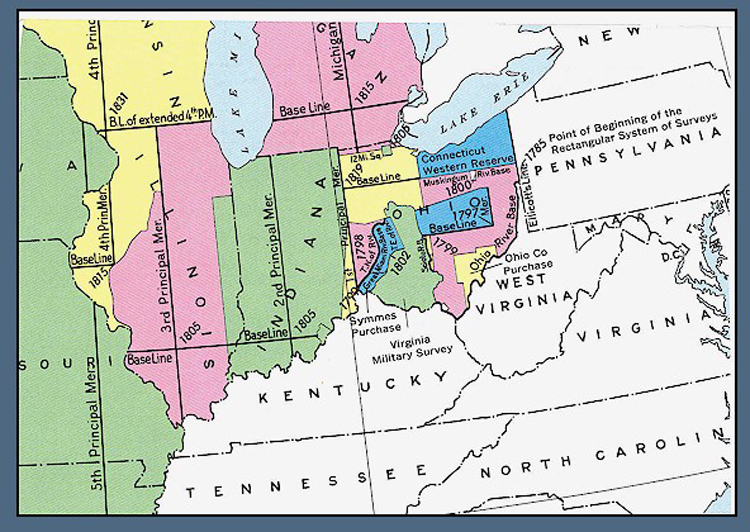

Courtesy of USBLM meridian map point of beginning

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:USBLM_meridian_map_point_of_beginning.jpg

Courtesy of Type 2 Clydesdale Cyclist:

http://type2-clydesdale.blogspot.com/2012/05/point-of-beginning-in-middle.html

Courtesy of http://www.flickr.com/photos/kv3x/2883352858/

Courtesy of Rock Springs Park

http://rockspringspark.blogspot.com/2012_04_01_archive.html

Courtesy of Rock Springs Park

http://rockspringspark.blogspot.com/2012_04_01_archive.html

Courtesy of Beginning Point of the U.S. Public Land Survey:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beginning_Point_of_the_U.S._Public_Land_Survey

CONTINUE TO The "Point of Beginning" Represents Much More than a Local Landmark

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.