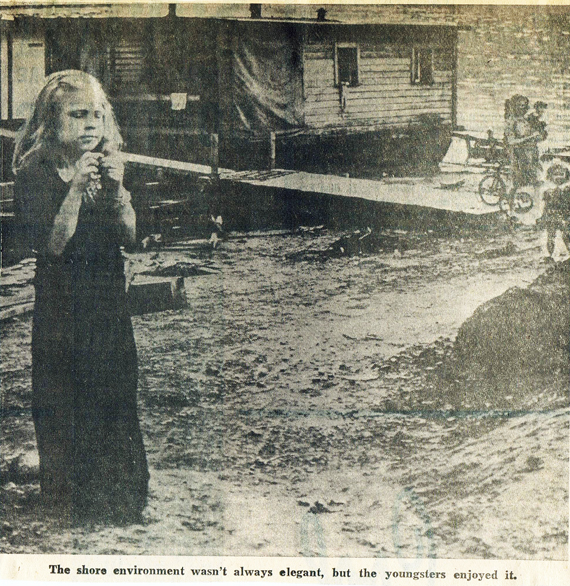

For some, rivers provided a place to live. House boats were a common sight along the banks of the Ohio River at East Liverpool from at least the latter half of the 1800's though the 1950's.

Happiness Was A Nice Houseboat

By Robert Popp

East Liverpool Review

Feature Pages

East Liverpool, Ohio, Saturday, July 13, 1968 -- page 8

No grass to cut, no snow to shovel, no hedge to trim, no real estate taxes to pay.

That was the happy status of the houseboat residents along the banks of the Ohio River a generation or so ago. Though they've all faded from this region now, prObably into the humdrum world of the land dwellers because of prosperity, the houseboat family was a unique and accepted part of the nverfront landscape for many years.

A heavy hawser secured the houseboat to a convenient stump, and a flimsy gangplank led from the front deck to the muddy shore. That was the houseboat man's only connection with the land of a mortgages, sidewalks and lawns and all tangibles that give dimension to the lives of the landlubbers.

HIS FRONT YARD was the broad expanse of the Ohio, green, quiet and shaded in the summer. ice bound at times in the winter, and angry, surging yellow during the annua1 spring flood.

Taking his cue from an earlier pioneering strain, he asked only to be left alone. He wanted no truck with outsiders, particularly the ones representing the police and the courts, and any stranger was viewed with serious suspicion.

If the bill collectors or police became too persistent, It was an easy matter to slip the hawser, pull in the gang plank and drift with the inshore current a few miles downstream to new scenery and a new address.

"Shantyboats," some people called them, and the word was an apt description of some of the floating residencestied to the Ohio and West Virginia shores. But others were as neat as any cottage set in a green lawn, with flower boxes on the rail, a fresh coat of sparkling paint and a rocking chair waiting on a spotless, deck.

The general architecture of a houseboat left little room for ingenuity in living arrangement. Rooms were connected by doorways end-for-end, since the necessary economy of space would permit no such extravagances as hallways. A narrow deck ran along one side or both, widening at either end into what passed for a porch. The whole thing rode on a flat-bottomed hull resembling a small scow.

ONE OR TWO coal stoves served for heating and cooking. Kerosene lamps sometimes furnished light, although in later years some of the more affluent houseboat dwellers managed utility hookups to the shore, providing themselves a with water, electricity and even telephones.

A flood was a time of crisis for the houseboat people. They doubled and redoubled the lines holding their craft to the shore. Often times the receding waters would leave a houseboat stranded on a flat shelf above the water line, to remain there until the next freshet lifted it back into the river again.

But the flood waters provided a bonus in the form of tangible property that could be had for the claiming. The houseboaters took to the river in skiffs and John boats to catch and beach all the myriad items that became waterborne in a flood - everything from assorted lumber and oil drums to tree trunks and chicken houses. Property carried away by the high waters was salvage, ripe for the picking.

The houseboaters' unique position - moored in West Virginia waters, but tied to the Ohio shore - led to all sorts of questions about legal jurisdiction that never were settled adequately.

THE LAND-BOUND majority looked upon them squatters, persons suspended in a legal limbo that was neither Ohio nor West Virginia.

That satisfied the houseboaters, all right, until it posed a serious problem on what schools their children should attend or which state should issue the relief orders. They didn't trouble themselves with voting and other acts tending to raise questions about legal residence.

It was a uniquely independent life, because the rest of the community forgot about the houseboat man unless he raised a real ruckus or flouted the law in a way that could not be ignored. Generally speaking, he was left to his own devices, free to accept the community's ways if he desired but free to get along by his own rules, if he wished.

Fishing helped with the food supply. And many of the houseboaters managed to raise lush little gardens in the fertile soil of the river bottoms. Some worked regularly, some didn't, but they managed to survive in undiminished numbers for several generations.

THEY CLUNG to their unusual habitats despite sporadic efforts in several communities to persuade them to untie their craft and drift away downstream. Local do-gooders pointed out the houseboats were moored on public property or worse yet --- private property. The U.S.1 Corps of Engineers regarded them as a navigation hazard and an eyesore along the shores, but they managed to evade a showdown with the federal government.

Affluence, or the waning of the pioneer spirit, finally did in the thinning ranks of the clan. The younger generations, with money in their Jeans, acquired homes on land like everybody else. The oldsters died off, or give up the river life for lack of stamina to meet its challenges.

So today not a single houseboat is moored along East Liverpool's shores. The word houseboat has come to mean a faetory-built aluminum craft on which landlubbers disport themselves on summer weekends, crusing the river with two heavy outboards on the stern, a cold drink in their hands and a multi-striped canopy overhead.

A housebont, eh? Not by any definition known to the old-timer who hammered his home together with driftwood and then rested while the wake of a passing towboat rocked him to sleep on the wide bosom of the Ohio.

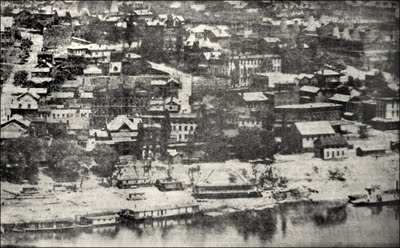

Various types of house boats are visible in the above 1898 photograph. This is the area between Broadway and Union Streets.

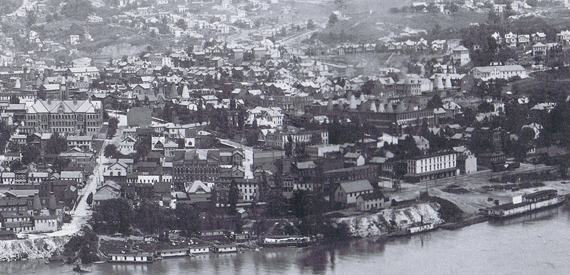

A little wider version of the above picture.

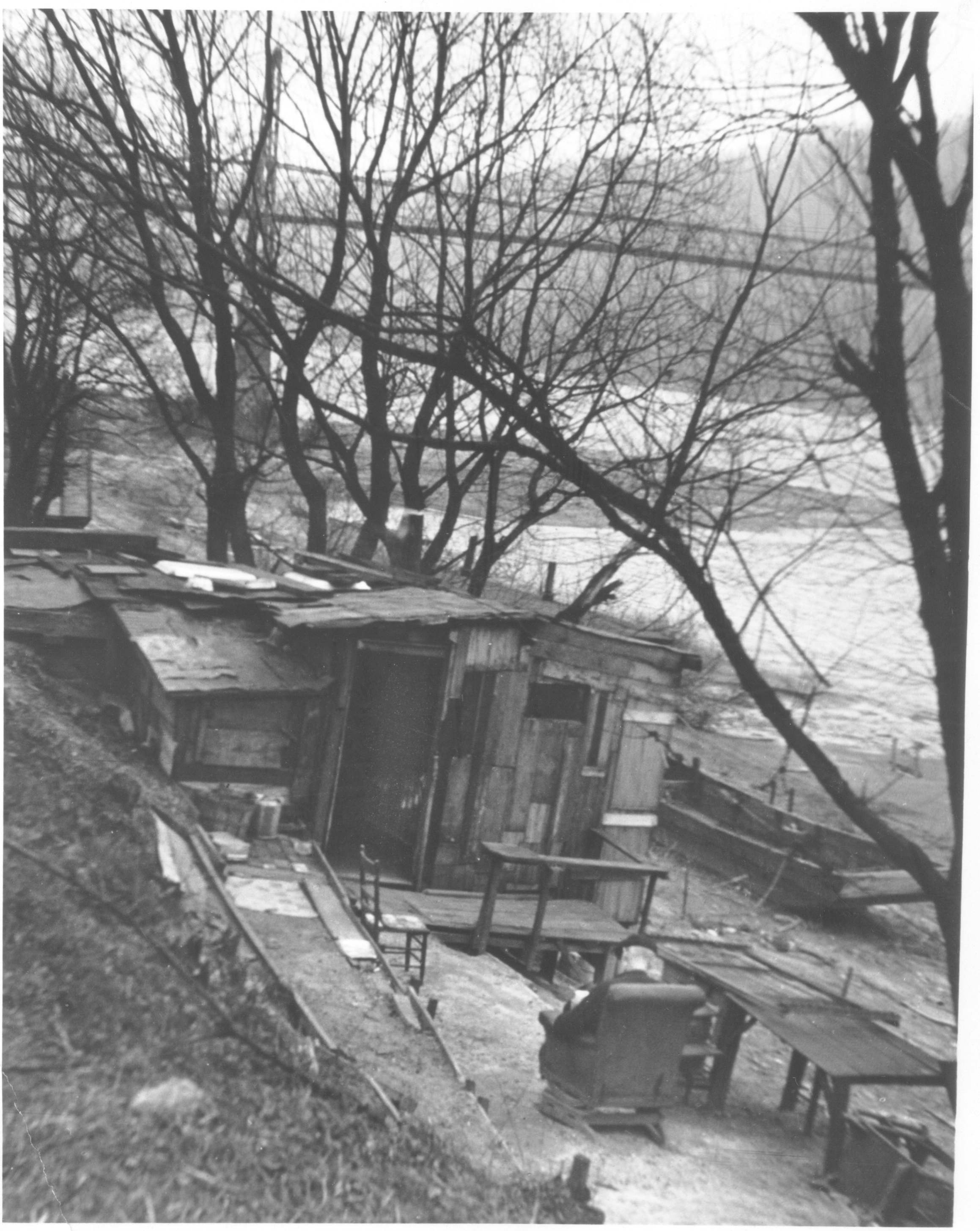

This is one man's home. While not on the river itself it sat on the bank just below the Newell Bridge.

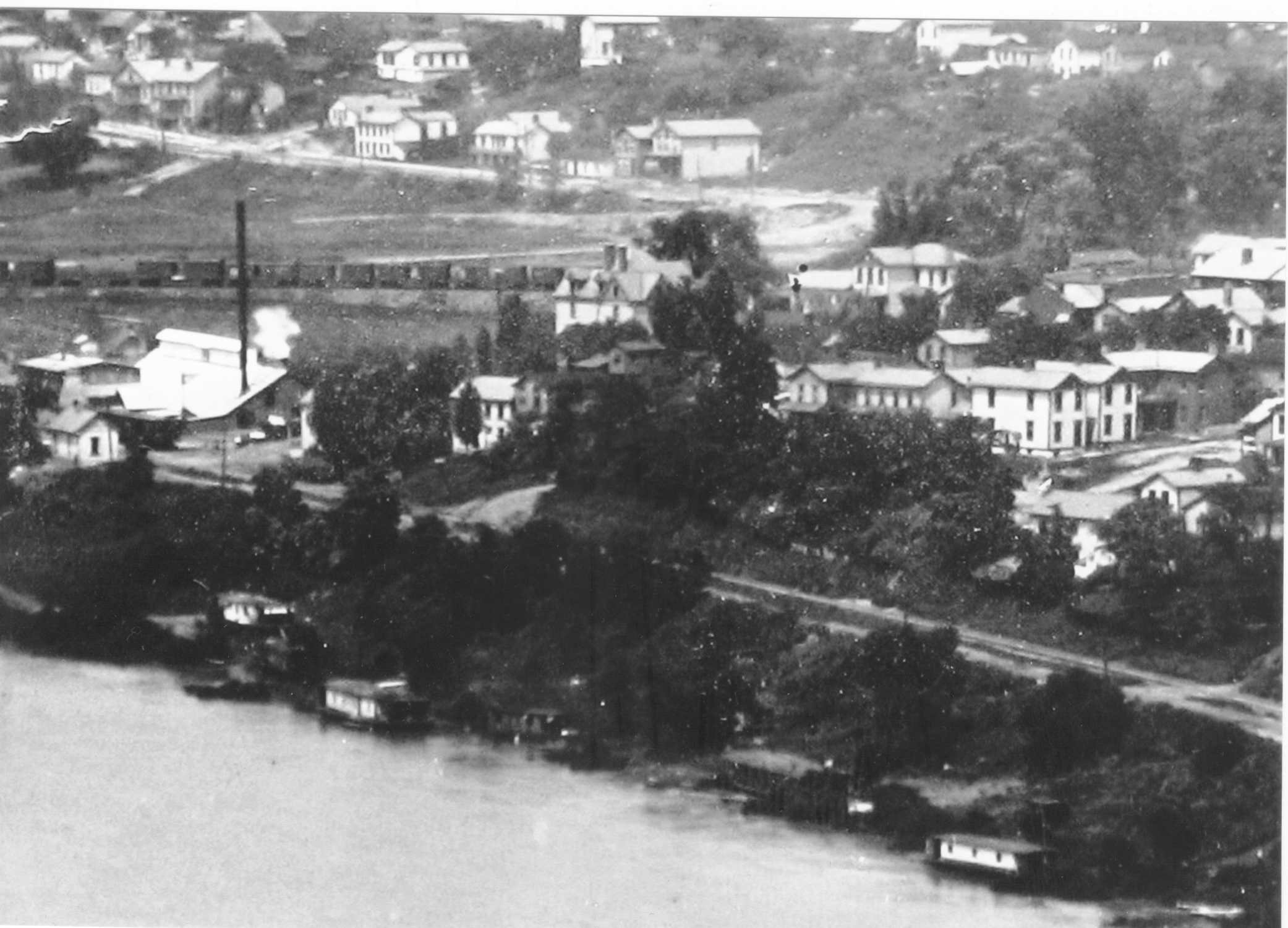

A couple of house boats are visible in this photograph. The date of the photograph is unknown. It is probably late 1890s and the area shown is the the west end of East Liverpool. Some of the identifying landmarks are in the background. To the left in the picture is the railroad Horn Switch. Behind it is what is now 8th Street. Between the Horn switch and the river in the left of the picture is the Golding & Sons Flint and Spar company. The Center of the picture shows the lower end of 4th Street. In a few years the Newell Bridge would be constructed in this area.

During floods a house boat could rise with the water as those in this picture have done.

House boat 1957. The bridge pier is for the Chester Bridge.

A house boat almost identical to the one shown above in much the same position in relation to the Bridge, only in this case it was the Newell Bridge, caught fire December 20, 1949. Two people, John Bayless and Evas Bailey died in the fire. Such were some of the hazards of living on the river what with basically candles or oil lamps and kerosene heaters for light and heat. Our thanks to Gary Cornell, retired ELFD firefighter and FD historian for looking up that information for us.

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.