The beginning

Many American communities eagerly sought and supported railroad projects which were slated to enter or terminate in their town. East Liverpool was no exception. With the prospect of increased real estate values and a rise in business activity as a result of improved transportation, many town boosters and speculators purchased stock in the railroad companies. In 1830 there were no railroads in the state of Ohio but by 1850 the total rail mileage had reached 590 and only ten years later soared to 2,946 miles of railroad in operation, the highest in the United States."

A railroad line connecting Lake Erie to the Ohio River had been sought by many residents of northeast Ohio for several years prior to 1835. Two routes were being considered, Painesville to Wellsville through New Lisbon, and Ashtabula via Warren to East Liverpool. Delegates representing both interests met in Salem to choose a route. The East Liverpool contingent arrived prepared to argue their case. Prior to the Salem meeting, on 17 October 1835, a group of local residents met at the home of William Thompson in Foulkstown to discuss the project. Eight representatives from East Liverpool arrived at the meeting with a survey of the local route in hand and a letter signed by many citizens declaring their route to be the "most favorable direction for the railroad in question." In addition, the group resolved to send a delegation consisting of Richard Boyce, Dr. Quigly, A.M. Dawson, Mathew Laughlin, and William Thompson to meet with citizens of Geauga County concerning the project."' When a compromise failed to materialize at the Salem convention, these men decided to apply to the state for a charter on their own. The charter was granted by the legislature and a bitter rivalry began. Since Wellsville was far in advance of East Liverpool in terms of development as a shipping point, its position looked strong. New Lisbon, important to the success of the project, was deeply involved in the Sandy and Beaver Canal project and did not lend any support to proposed competition. The route terminating in Wellsville was temporarily abandoned.

The Ashtabula, Warren and Liverpool Railroad Company was chartered in February of 1836. Its incorporators, who included six men from Ashtabula County, seven men from Trumbull County and John Smith, Elderkin Potter, David Hanna, John Patrick, John Dixon, and William G. Smith of Columbiana County, set about selling shares of stock. Locally, a committee met at Aaron Brawdy's house in East Liverpool to discuss ways in which they should pursue their undertaking. According to the charter, the company was authorized to sell capital stock worth $1,500,000 in shares of fifty dollars each. Construction could begin once fifty thousand dollars was subscribed. The charter also specified that if the railroad was not completed within twenty years, the act would be considered null and void. On 11 March 1836 the committee published an announcement in a New Lisbon newspaper about the proposed railroad and the fact that stock was available. In describing the importance of the railroad, they stated that it would intersect the Sandy and Beaver and the Ohio and Pennsylvania canals. It would also intersect the Cleveland and Warren Railroad and the proposed railroad from Pittsburgh to Cleveland connecting on the Ohio River at "... some favorable point in Columbiana County ....They added that this great project would then link New York with the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, "... at less than one-half the expense incurred by the present mode of canal navigation." The route, which had already been surveyed, would terminate in the town of East Liverpool, "... the location of which is equaled by few, and surpassed by none on the Ohio in any respect ....This proclamation was, of course, untrue. It was, however, exactly the type of boosterism the river town required to stimulate its growth. The committee also recommended the project to investors as "safe, profitable, and advantageous

The commissioners began to sell stock subscriptions locally and in Pittsburgh and New York City. Many local residents, including Claiborne Simms, purchased shares.'2' By the end of March Richard Mansley had disposed of half a million dollars worth of stock to one New York firm and the company announced that fifteen miles of the southern division would be put under contract immediately. The newspaper also reported that ". . speculation in property in the town of Liverpool (the southern terminus of this road) is quite rife." This speculation in property was the result of William G. Smith's ingenious plan to sell stock in the proposed railroad at the same time he was bolstering his considerable personal interests in East Liverpool.

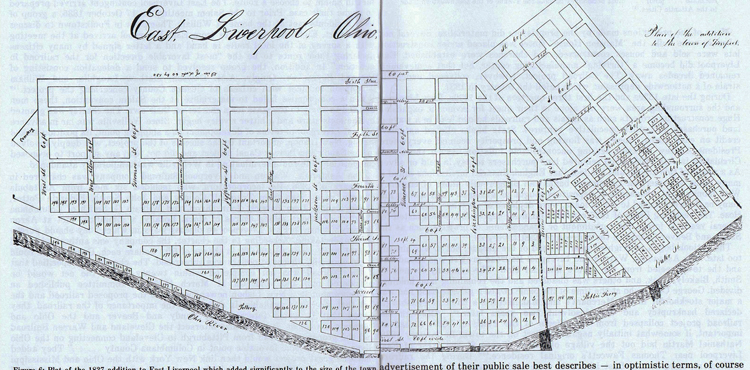

Actively involved in pushing the proposed railroad project to completion, Smith laid out an addition to the town in 1836. The additional lots encompassed

Figure 6: Plat of the 1837 addition to East Liverpool which added significantly to the size of the town. Note that Cook (now Third) and Robinson (now Fourth) Streets were named after two of the Pittsburgh investors. Note also that Broadway was originally named Railroad Street in honor of the coming Ashtabula, Warren and Liverpool Railroad. The City of Hills and Kilns pp 24-25.

approximately an acre of land."' He had purchased this land and an additional tract comprising about sixty-seven acres several years earlier. Smith enticed several wealthy Pittsburgh speculators, including George A. Cook, Lawrence Mitchell, and James Blakely, to purchase property from him as a bonus for taking stock in the new railroad project. Deeds dated 17 March 1837 indicate that Smith received at least $3,500.00 from these individuals for a two-thirds share of about 104 total acres.'23 He retained the remaining interest for himself. James Blakely, who already owned over 140 acres of land north of the platted town which he had purchased from Simms the year before, became a prominent landowner."

The new proprietors formed a joint stock company and on 11 May 1837 advertised the public sale of 128 of the 134 lots in their addition. This addition was located at the eastern boundary of the town (figure 6). It began at Union Street and ended at the alley just east of College Street. The proprietors' advertisement of their public sale best describes - in optimistic terms, of course - the importance of the railroad project, the opportunities available in East Liverpool, and their efforts to develop the town.

These lots are beautifully situated on the Ohio River . . . fronting on a street 100 feet in width, and in that part of town in which shortly the heaviest business will be transacted. Wharves and landings can be constructed in front of these lots - (and in fact fronting the whole town, equal to those of Cincinnati or Pittsburgh) - a wharf having been made by the proprietors during the last season, at which the largest class of steamboats load and unload with ease. The plan on which this property is laid out is on a liberal scale, with streets of sixty, eighty, and one hundred feet wide; and large plots have been reserved for places of worship, public squares, and manufactories. The undersigned bind themselves to devote one-fifth of the proceeds of the sale to the erection of an extensive Hotel, and for the extension of the wharf and landings opposite the property offered for sale . . . Liverpool is . . . in the midst of a rich and flourishing agricultural district, having within six miles, eight large flouring mills - and with the exception of the county of Hamilton, the largest in population in the State. Coal, stone, lime, clay, and other materials, for building and manufacturing are in abundance in its neighborhood; and capital and enterprise are only wanting to make it in a few years as thriving a manufacturing and mercantile town as any in the state The Ashtabula, Warren and Liverpool Railroad . . . will, when finished, be one of the most important public works in the state land . . . [and] . . . must necessarily become the avenue of the southwestern trade to the Atlantic Cities."'

Many of the predictions made by the proprietors did materialize. Several new wharves were built, the "Mansion House" Hotel was placed under construction, lots were sold and houses constructed, and churches were established. East Liverpool did become a "thriving" manufacturing center, but that achievement remained decades away. The railroad project, however, collapsed under the strain of a nationwide depression which befell the country in 1837. The City of Hills and Kilns Life and Work in East Liverpool, Ohio William C. Gates. East Liverpool Historical Society, (1984) pp. 22-26.

With the pottery industry booming, the construction of a railroad provided East Liverpool with its long-awaited link to the rest of the nation. Not only did it provide speculators with additional incentive but it directly benefitted the community with both short-term advantages and permanent gains.

The Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company was originally chartered on 14 March 1836 to construct a road from Cleveland to a point in the direction of Pittsburgh "... on the State line between Ohio and Pennsylvania, or on the Ohio River." Because of the Panic of 1837, construction was not begun and the project was not revived until 1845 when the charter was reissued. Agents for the company canvassed the towns and areas on the proposed route seeking support and subscriptions. East Liverpool citizens held a meeting on 22 January 1847 at the home of Aaron Brawdy to discuss the issue. With John S. Blakely, one of the incorporators of the company in the chair, they resolved to aid the railroad company in securing a right-of-way along the river between Wellsville and the state line above East Liverpool. Wellsville, the southern terminus of the line from Cleveland to the river, also enthusiastically endorsed the project and proponents set about raising the necessary capital. Construction on the main line, as it was known, began in July of 1847. John Thomas wrote in 1847 that "the Rail Road leaver [sic] at Present is sume [sic] what rageing." Progress was slow until 1849 when the entire line from Wellsville. to Lake Erie was put under contract. The company obtained legislative permission from Pennsylvania in 1850 to extend its line to Pittsburgh. In July 1851 another meeting was held in East Liverpool in which James Blakely and C. Prentiss, president of the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company, addressed the crowd concerning the benefits of the project to the town. George S. Harker, Stockdale Jackman, and Blakely were appointed to solicit sales of stock.

On 14 February 1852 the construction of the railroad line to Wellsville was completed, and within a few days the first freight train rolled over the rails from Cleveland to the Ohio River terminus. The editor of the Wellsville Patriot proclaimed "This, certainly is a great achievement in our history, and one for which every citizen should feel proud ....86 East Liverpool potters and traders could now transport goods the three miles to Wellsville and ship them to points north. As evidenced by the earlier discussion, enthusiasm continued to run high and speculation was rampant concerning the railroad now only a few miles away. Optimism subsided, however, when it was learned that construction of the branch line from Wellsville, through East Liverpool, to Pittsburgh would be delayed because of a lack of capital. Near the end of 1854 the company was able to sell $150,000 worth of additional bonds in Hartford, Connecticut and prospects brightened. By September of 1855 the branch line, termed the Beaver (Pennsylvania) extension, was under contract and being constructed "with vigor." General contractor J.B. King and Company subcontracted locally with Gaston to grade and construct the railroad from Walker's brick yard (just south of town) to Harker's pottery, which was located near the Ohio River north of the corporate limits. The completion of the extension was eagerly awaited by residents and manufacturers alike. Potters suffered materially from delays in shipments because of low water in summer and the river's being icebound during much of the winter season. By September 1856 cars were operating over the extension and East Liverpool finally had its railroad."

The arrival of the railroad and the telegraph, which soon followed, was a great boon to East Liverpool. It opened new opportunities for the emerging clay industries. Steam locomotives linked them to national rail connections and allowed local potters to reach more distant markets with their Rockingham and yellow ware products. In 1861 the Baggott brothers boasted that their products were "... accessible by C.&P.R.R. to the entire North, and by 0. River to the South and West."" While the completion of the railroad was not the major turning point in the prosperity of the Ohio River town, it was certainly significant. For East Liverpool it was the pottery industry which changed the local economy, determined the makeup of the population, provided the impetus for the growth and development of the community, and began the transformation to an urban and industrial environment. The railroad, however, did augment the local industry and provided an important means by which it could expand and mature. The City of Hills and Kilns Life and Work in East Liverpool, Ohio William C. Gates. East Liverpool Historical Society, (1984) pp. 53-55.

The regulation of railroad lines and switches, once they entered the corporate limits, also fell to the municipal government. As early as 1880 pottery manufacturers and other citizens of East Liverpool expressed the need for an additional railroad line connecting the city with other established routes. Throughout the 1880s several railroad companies were approached in an attempt to secure an additional line; however, for a variety of reasons none of the proposals came to fruition. Some railroads were simply not interested, while others, impressed with the amount of freight shipped and received, requested that the community or local investors assume partial financial responsibility for the construction of a new line. While many people understood the need for a competing line, in 1878 the consensus of opinion was that the money requested by the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad would be difficult to raise because almost all available capital was being invested in the pottery industry. Some residents believed that city monies would be better spent on street paving and a sewage system rather than investing in a railroad.

Even though a second railroad line did not enter East Liverpool, additional track was constructed within the city by the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company in 1887. The way in which the "Horn Switch" and one of its extensions came into existence demonstrates the influence of the potteries in East Liverpool. In January 1887, undoubtedly at the request of several local pottery firms, the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad Company asked council to grant a right of way to build a side track off the main line along the river and through the upper part of the city to reach the potteries in that area. The following month city council met in special session to consider the proposal. Homer S. Knowles, representing Knowles, Taylor and Knowles, told council that his firm was contemplating the construction of a large china works and would like the promise of better railroad facilities before proceeding. Council adopted a resolution approving the action that evening and two weeks later passed an ordinance authorizing construction of the new switch. Following passage, Mayor John Burgess stated that there were two things in East Liverpool, "potteries and people, each mutually dependent upon each." The "Horn Switch," which connected the "Dresden" and five other potteries to the main line along with K.T. & K.'s new china works, was constructed.

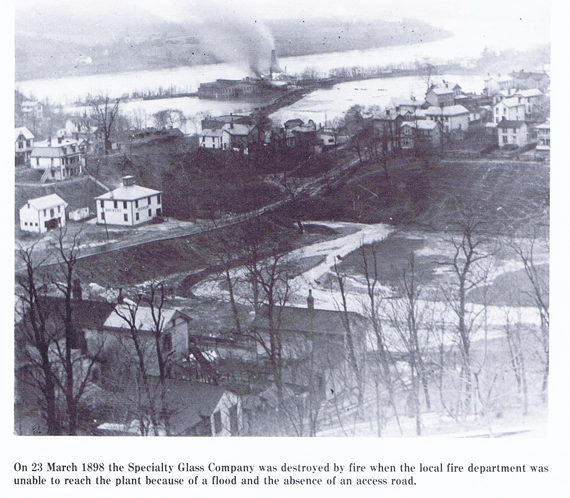

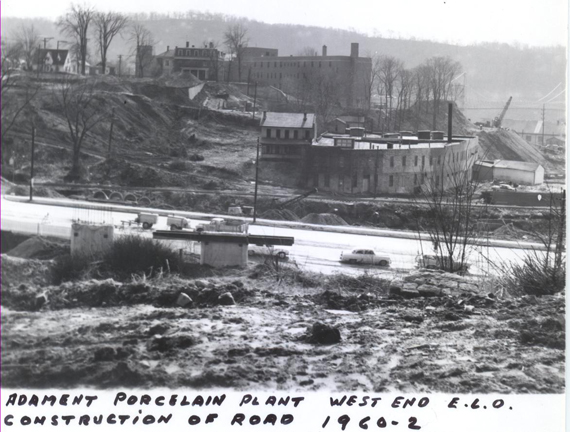

This picture should help people locate the beginning of the "Horn Switch." The High ground running towards and behind the Glass Factory is the main line of the existing railroad of that time. The high ground to the right of the Glass Factory coming forwards in sort of a leg of a V is the "Horn Switch" headed towards what is now the 4 lane Highway, 8th Street, Routes 7 and 39.

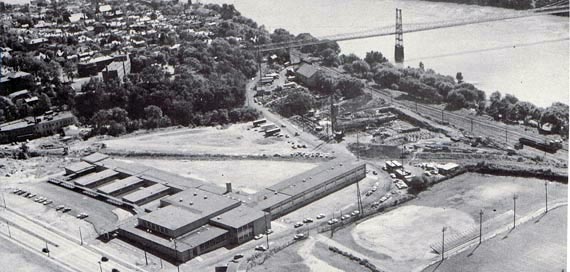

Across the center of the picture you can see what appears to be a line. That is actually the Horn Switch Spur. This picture was 1955-56 time period.

On 7 January 1888 the city awoke to a new extension of the switch laid over a five hundred foot section of Apple Alley backing on the potteries of Knowles, Taylor and Knowles, the Standard Co-operative Pottery Company, and the Goodwin Brothers. This unapproved act "caused something of a sensation." These three firms and the railroad company had made "informal overtures" to council to lay the track (which could be used by any present and future railroads) at their joint expense, but council was unwilling to grant an exclusive franchise of public property to them. The pottery manufacturers and the railroad company took matters into their own hands and installed the tracks during the night. Upon discovery of the tracks, council ordered the street commissioner and a crew to remove the track and sent policemen along to guard them. By noon fifty feet of track had been removed. City officials and the pottery owners agreed to suspend these operations until the next council meeting the following week. At the meeting city solicitor Mackall argued that whatever was in the interests of our potteries was clearly in the best interest of the entire city. Councilman Hanley saw the controversy in a different light. He stated that the issue was not whether the firms should have the privilege or not but that it was council's duty to protect the citizens and stand as a barrier against unlawful acts. Homer Knowles admitted that the firms had transgressed the letter of the law but made no excuse for theft procedure. Knowles then told council that his firm had been offered a bonus of fifty thousand dollars, four acres of free land, and the advantage of four railroad lines by another community, but K.T. & K. declined in favor of East Liverpool. Following this obviously moving presentation, council voted unanimously to rescind their order calling for the removal of the track. In February 1888 council passed an ordinance granting the right to lay the track on Apple Alley and also allowed the Burford Brothers Pottery and the Potters Cooperative Company to lay side track from the new switch. The editor of the Review endorsed council's actions and reminded readers that - the potteries have been the making, and still are the life of our town .." The City of Hills and Kilns Life and Work in East Liverpool, Ohio William C. Gates. East Liverpool Historical Society, (1984) pp. 120-121.

In this 1897 picture you can see the Horn Switch in the background. In the lower left of the picture is the Flint Mill. Interestingly enough the Oliver Burford House (One of the three brothers who owned the Burford Brothers Pottery and one of the destinations of the Horn Switch Spur) is the big house a little above and to the right of the Flint Mill. It is the house with the two chimneys and two dormers visible.

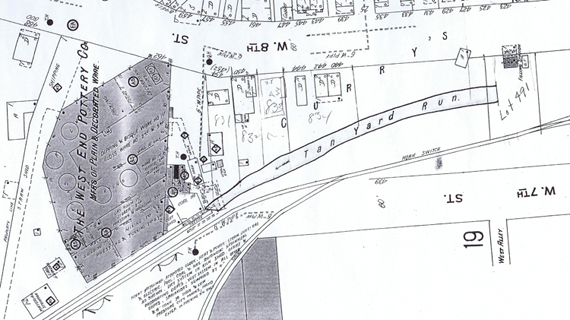

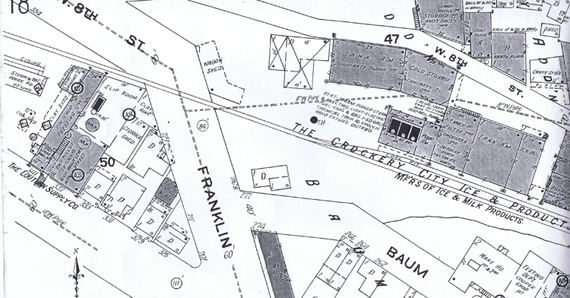

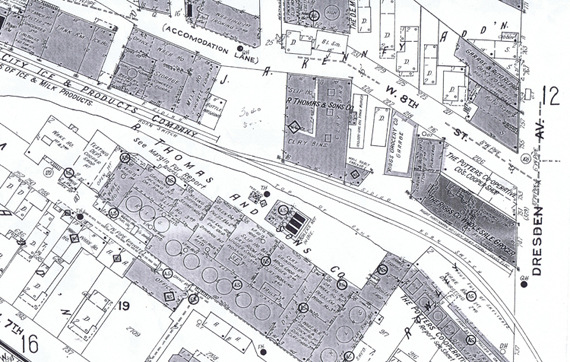

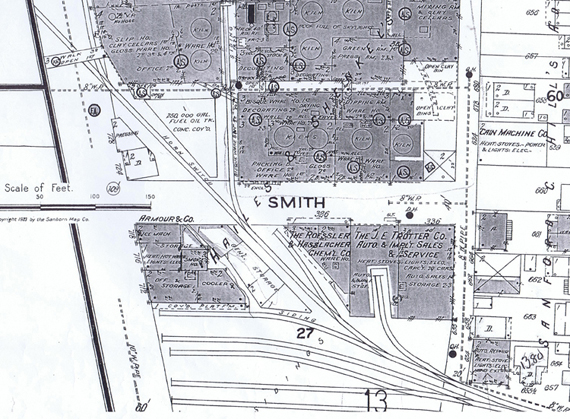

This and the other 5 maps of this style are all from the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1923. We pick up the Horn Switch spur as it nears 8th Street.

This and the picture below fits the above map. However, the West End Pottery no longer existed in the 50s or 60s. The pottery in the picture is the Adamennt Pottery which just begins to show up on the map lovew right had corner.

Crossing West 8th and running along the building on the north side of West 8th street, (Webber Way).

It approaches and crosses Dresden Ave.

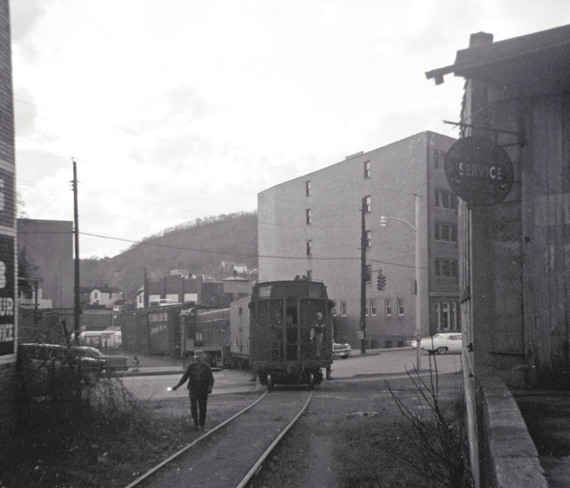

PRR local WE-101 along Webber Way, probably switching Riggs Co. across street to the left, East Liverpool, OH, 4/13/1965. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

PRR local WE-101/102 on Horn Switch, Dresden Ave. yards, April (7, 13, or 14) 1965. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

PRR local with caboose ("cabin") sitting on Horn Switch "main" track while crossing Webber Way to reach Riggs Co., East Liverpool, Ohio, April (7, 13, or 14) 1965. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

PRR local spots car at Riggs Co., East Liverpool, Ohio, April (7, 13, or 14) 1965. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

PRR Local WE-101 on Horn Switch, shoving caboose-first across Dresden Ave., April (7, 13, or 14), 1965. The crewman (probably brakeman or conductor) walking ahead of the train carries a flare to draw the attention of motorists as he stops traffic at crossings. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

Connects to the various Dresden Ave Potteries as well as the former Burford Bros Pottery. The Pottery north of the word SMITH was the former Burford Bros. Pottery.

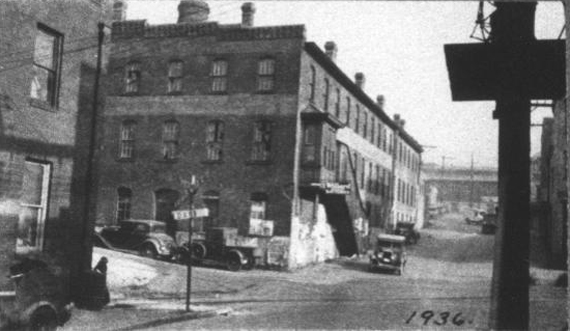

The East Side of Dresden Ave. You can see the tracks. This was 1936.

The Pottery there was the former Burford Bros. Pottery. They sold to another company in the early 1900s.

PRR local WE-101/102 on Horn Switch, Dresden Ave. yards, April (7, 13, or 14) 1965. I believe the alley being crossed is Green Lane. Camera is pointing toward St. Clair Ave. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

PRR local WE-101/102 on Horn Switch, Dresden Ave. yards, April (7, 13, or 14) 1965. I believe the alley being crossed is Green Lane. Camera is pointing toward St. Clair Ave. Picture and comments courtesy of Jeff Pletcher.

Railroads in and around East Liverpool 2

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law

though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.