| This article originally appeared in the 1984 Pottery Festival Souvenir Program. The author is Timothy R Brooks. |

East Liverpool, in early 1918, was a city adjusting to both wartime excitement and adversity. War, declared on Germany less than a year earlier, met with the broad approval of the city's predominant ethnic group - the English emigrants from the Staffordshire pottery district and their descendants. For several months in 1917, East Liverpool even boasted a British army recruiting station, which sought enlistments among the area's many British subjects.

The Conscription Act had been in full swing for some time with the first contingent of draftees leaving the city on September 7, 1917, and other groups leaving regularly since that date. Company E, the city's volunteer infantry company, had marched to the railroad station on Sept. 10, 1917. This unit was led by Captain William M. Hill, who had also led an earlier Company E during the Spanish American War in 1898. By early 1918, several hundred city men were in training camps preparing for the eventual voyage to France and the trenches

Locally, citizens enthusiastically supported Liberty Bond drives and listened to the exhortations of "Four Minute Men". These specially selected orators delivered brief patriotic speeches at movies, theatrical productions, or, wherever a crowd could be found. Propaganda against the brutal "Hun" was widespread. Residents viewed films such as "The Tanks in Action" or "The Kaiser-Beast of Berlin".

Despite the martial overtones, no one anticipated that the city's relative calm would soon be broken by cries of sabotage, arson and murder which would leave residents looking nervously over their shoulders for enemy agents who might bring further death and destruction to the community.

At about 5:00 a.m. on the morning of February 7, 1918, William Bailey, an employee of the streetcar company, noticed flames leaping from the southern end of the Adamant Porcelain plant as he passed over the West End viaduct. He immediately stopped and telephoned the alarm to the Central fire station. Fire Chief Thomas Bryan later recounted that as the department responded, he could see the illuminated sky over the West End filled with sparks.

|

| Map showing location of fire. Click here for larger view. |

By the time the department arrived, the entire 115' x 275', two-story structure was in flames and the firefighters found it impossible to save the plant. The heat was so intense that two nearby houses were consumed and the wooden ties on the viaduct above the south end of the building caught fire and were extinguished with chemicals. The department fought the blaze for more than three hours before bringing it under control.

The complete destruction of the Adamant Company's five-kiln electrical porcelain plant forced approximately one hundred persons out of work. The firm had obtained several government contracts. An "extra" edition of the Review on February 7th noted that, "Although the company is said to be working on war orders, officials do not suspect alien enemies of starting the fire."

More startling to city residents than the fire itself, were the horrors discovered in the rubble later in the morning. Shortly before 11:00 a.m. a charred human torso described as missing head, arms and legs was discovered next to kiln no. 3. Half an hour later, a second body, similarly burned beyond recognition, was found near kiln no. 5.

|

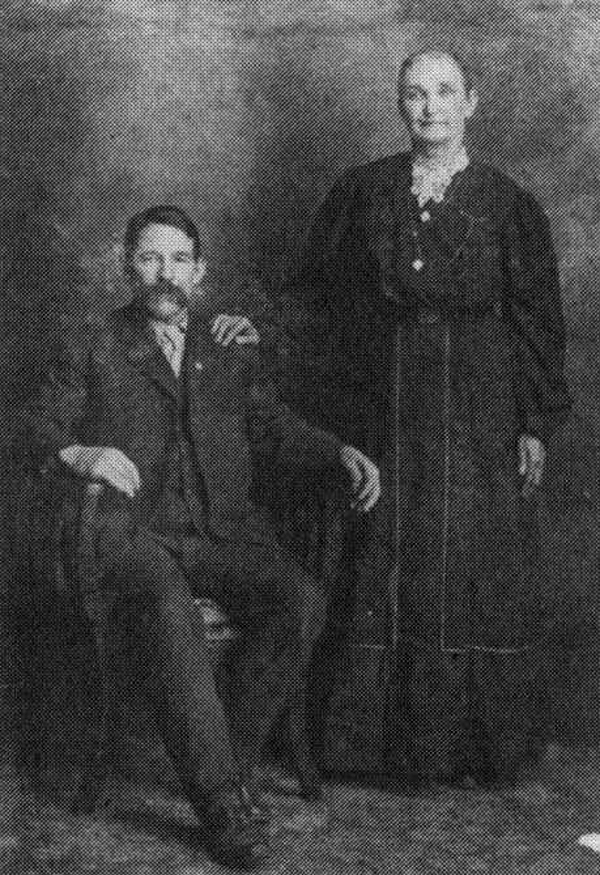

| Photo of murder victim, Donald Mumaw, and his wife Sophia. Courtesy of David K. Mumaw and family. |

At the time of the fire, owner Harry Peach explained, only 60 year old night watchman David Mumaw was on duty. Due to a gas shortage, Peach added, no kilns were lighted. Mumaw's son, Carl, an engineer at the plant, attempted to identify his father's remains at the C.N. Miller Morgue but was initially unable to do so. According to descendants, final identification was only made through a Knights of Pythias medallion worn constantly by watchman Mumaw. The second body was identified as being that of Joseph Cannon, 55, a potter who had been sleeping at the plant for several nights and who proved to be missing after the fire.

Fire Chief Bryan stated that he doubted the cause of the fire would ever be determined. In his opinion, the two victims had probably been suffocated by smoke as they sought the exists. Harry Peach similarly discounted any suggestion of arson and promised that the plant would be rebuilt even though the estimated loss of $100,000 was only partially insured.

A single fire, even one with the tragic consequences of the Adamant fire, would not have been long considered newsworthy, but on the evening of February 8, a second major conflagration struck the area under suspicious circumstances. The Kenilworth Tile Company factory located at Third Street, Newell, was the next victim of the flames. Night watchman Frank Stanley was the only employee in the plant and, like the Adamant works, no kilns were burning. Stanley was reportedly in the opposite end of the building when the fire broke out in the drying room, which had been checked less than fifteen minutes earlier.

The flames spread rapidly and were soon being fought by both the Newell volunteers and a flying squad from East Liverpool. Firefighters quickly realized that they could not save the wooden portion of the plant and confined their efforts to saving the section of the plant containing the machine shop and the offices. The fire was brought under control by 11 o'clock, but not before two-thirds of the building was destroyed resulting in an estimated loss of $60,000.00.

The Kenilworth plant had also been awarded several war orders for electrical porcelain. The striking coincidence of the two similar fires in as many days led the Review to speculate that "enemy plotters may have been responsible...".

Two days later, disaster nearly struck a third time but was averted by the vigilance of another night watchman who was perhaps alerted by the previous fires. Frank Higgins, watchman at the R. Thomas & Sons works on Baum Street, East Liverpool, was making his rounds at about 2:00 a.m. Monday, February 11, when he noticed a shadow beneath one of the clay bins in the slip house. Quickly making use of his flashlight, Higgins saw a man bearing down on him. He drew his revolver and kept the individual covered until Captain Toland of the East Liverpool Police Department placed the man under arrest on a charge of being a suspicious person.

After his arrest, the man, who identified himself as Willis Payne from Proctorsville, Ohio, was imprisoned in the city building at Third and Market Streets. The succeeding days' race-conscious newspaper accounts described Payne as a negro with Mexican and Indian blood. Importantly, it was not at first suspected that he might have some connection with the still unsolved Adamant and Kenilworth fires.

|

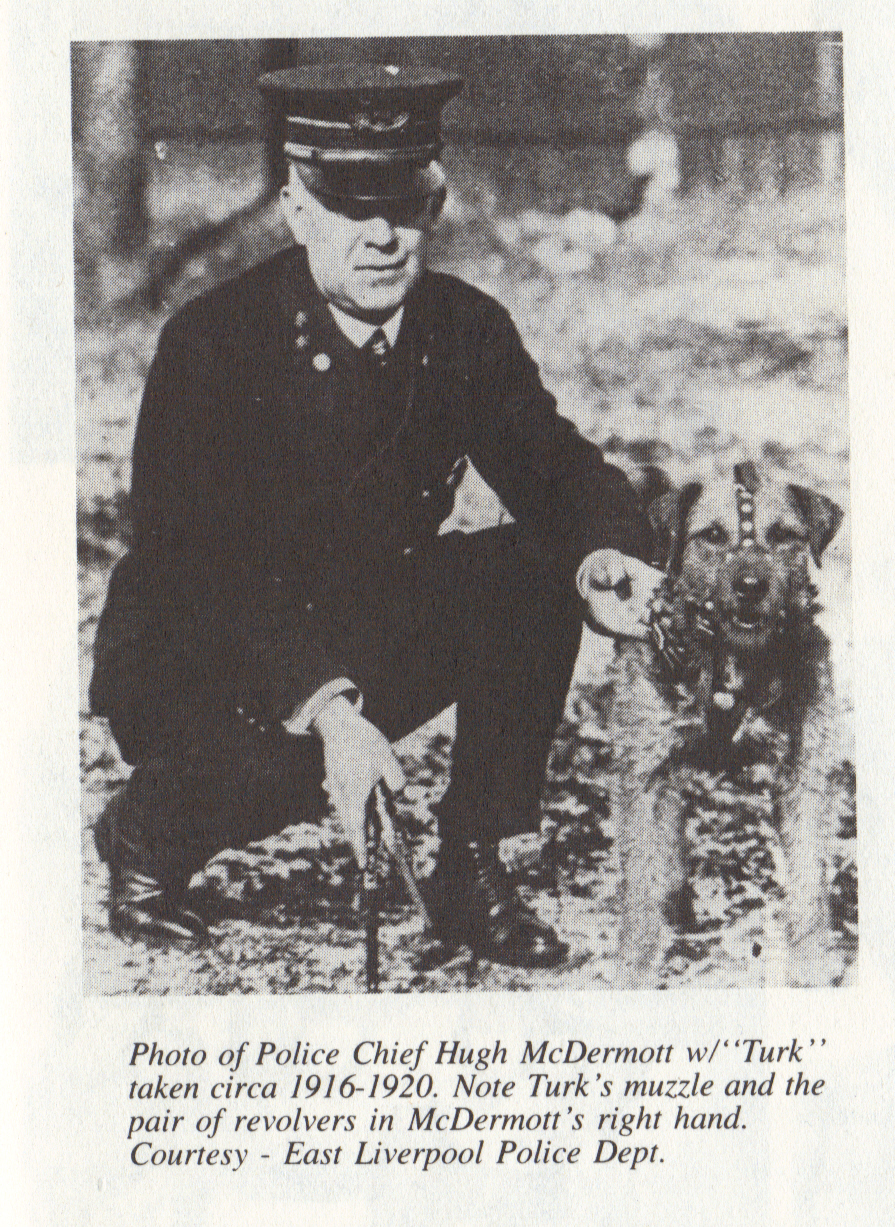

On the arrival of Police Chief Hugh McDermott the next morning the interogation of Payne took on a more aggressive aspect. At the arraignment before Mayor J.S. Wilson, Payne at first refused to answer any questions put to him. At some point during these proceedings, however, McDermott's airedale terrier, "Turk", lunged at Payne who, thus encouraged, immediately confessed to setting both fires.

McDermott and City Solicitor R.G. Thompson had conducted a two-hour examination of Payne which was transcribed and published in the Review. The interrogators soon realized from Payne's responses and especially from his conflicting stories that he was not in possession of the normal intelligence. The Review commented on his "parrot-like testimony" and speculated that he might simply have been a tool for an enemy agent.

It became apparent that regardless of motive, Payne was responsible for both the fires and knew details as to their origin. At various times during the questioning Payne indicated that another man had "put him up to" setting the fires. At one point, he stated that he was paid fifty cents to burn the Adamant Plant. Conversely, he later stated that he was trying to find work in the plants and when turned down was simply trying to get even. He even claimed that he had been employed at the Adamant work for a time, but owner, Harry Peach, denied ever hiring him.

Payne gave the police the name and a Midland address of the man he said had paid him, but this was not disclosed in the Review transcript as the police were hoping to make an additional arrest.

With regard to the murders of David Mumaw and Joseph Cannon, Payne denied seeing the latter, but claimed he had struck Mumaw in the head with a hatchet. Fire Chief Bryan confirmed that a hatchet had been found next to Mumaw's corpse but no wounds could be discerned. At one point, when asked why he liked fires, Payne responded, "Like to see the firemen working; like to see the blaze and if anyone is caught in them, like to hear the screams".

During the afternoon of February 11, Police Chief McDermott and Fire Chief Bryan took Payne to the scenes of both fires. At the Adamant site, Payne showed both officers where Mumaw had been struck down. Bryan stated that the spot pointed out was the exact location where the night watchman's body had been discovered the next day. In Newell, Payne was identified by watchman Stanley who claimed to have run him out of the plant some time before the fire was discovered.

Charges of arson and murder were filed against Payne after the return to East Liverpool and that news, as well as details of the confession, spread immediately throughout the city. Fearing that some attempt might be made to lynch the prisoner, city officials transported him to the Lisbon jail in the 5 o'clock Y & O car.

Before he was removed from the city, Payne told the authorities that he had intended to kill the watchman at the Thomas plant and then burn the structure. After the destruction of the Thomas works, he said he planned to similarly burn the Davidson porcelain works at the corner of Sixth and Broadway. All the potteries mentioned by Payne were working on war orders and this led officials to the reasonable conclusion that enemy plotters were behind the crimes. Payne further described his suppose accomplice as being "tall and wore a fur overcoat".

By the evening of the 12th, it had been learned that Willis Payne had been committed to an institution for the feeble-minded in Columbus in 1912 and had only been released in January, 1917. Relatives of Payne in Wellsville came forward and stated that his mental condition was such that he could be persuaded to commit any crime.

The suspected connection with the Kaiser's spies was still being pursued and the federal authorities at Cleveland were contacted. Together, federal secret service agents, deputies from the State Fire Marshall's office and the local police authorities all vigorously searched for "higher ups" who might have directed Payne's activities.

While incarcerated at Lisbon, Payne proved a cooperative prisoner, though continually maintaining that he had killed Mumaw and started the fires. Sheriff Dalrymple reported that he had also confessed to setting the Chicago fire. Not surprisingly, all those who conversed with Payne since his arrest agreed that he was insane.

Columbiana County Prosecutor Walter Beck put his office to work preparing the case against Payne. On February 15, Beck and his assistant W.H. Vodrey spent the day here viewing the sites and interviewing witnesses. Beck commented, "We intend to follow every possible clue until all the facts in the case have been secured." Beck stated further that the determination whether to prosecute Payne would depend on the outcome of the investigation and a possible examination of the prisoner's sanity.

A partial alibi advanced by friends of Payne in Lisbon was completely discounted when a Mr. Coleman of Leetonia, who worked as a conductor for the Y & O Railroad, positively identified the prisoner as the same man who boarded his car bound for East Liverpool on the night of the Adamant fire.

On the 19th, the Review reported that a special session of the grand jury would not be called, at least until the state officials completed their investigation. Additional relatives of Payne, including an uncle from Proctorsville, confirmed that he had been mentally unbalanced since birth.

After the brief article on the 19th, the Payne story apparently ceased to be front page news. No further accounts of the fires or the various investigations are found. No prosecution ever occurred and the arson and murder charges were eventually marked "Ignored by Grand Jury".

On April 29, 1918, an "Inquest of Lunacy" was held in the Probate Court which resulted in an official determination that Willis Payne was legally insane. Accordingly, in early May, Payne was transmitted to the Hospital for the Criminally Insane at Lima for an indefinite term.

No "higher ups" were ever arrested. If the "man in the fur overcoat" was, in fact, a German agent responsible for encouraging Payne to commit his crimes, he escaped from the clutches of the police and from the effective interrogation tactics of "Turk".

The Adamant plant was rebuilt and would later be known as the Peach Porcelain Co., which would also be destroyed by fire in 1931. In 1932, the Ceramic Specialties Co. took over the site and continued in business through the 1940's. In the mid-1950's, the building was razed for the construction of the freeway.

The Mumaw family remained in East Liverpool with both David Mumaw's son and grandson working at the same plant where their relative had been so hideously murdered. A great grandson, named for the murdered night watchman, is now a Detective with the East Liverpool Police Department and has generously assisted in the preparation of this article.

The man responsible for breaking the Adamant case, Police Chief Hugh McDermott would remain the head of the department for nearly thirty more years before his retirement. His constant companion "Turk", who helped fight crime in East Liverpool for a total of twelve years, died on April 17, 1924

For pictures of the fire, a couple principle "players" in the event and day after the fire picture:

This site is the property of the East Liverpool Historical Society.

Regular linking, i.e. providing the URL of the East Liverpool Historical Society web site for viewers to click on and be taken to the East Liverpool Historical Society entry portal or to any specific article on the website is legally permitted.

Hyperlinking, or as it is also called framing, without permission is not permitted.

Legally speaking framing is still in a murky area of the law though there have been court cases in which framing has been seen as violation of copyright law. Many cases that were taken to court ended up settling out-of-court with the one doing the framing agreeing to cease framing and to just use a regular link to the other site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society pays fees to keep their site online. A person framing the Society site is effectively presenting the entire East Liverpool Historical Society web site as his own site and doing it at no cost to himself, i.e. stealing the site.

The East Liverpool Historical Society reserves the right to charge such an individual a fee for the use of the Society’s material.